Dr Clare Materia Medica

Introduction to the Dispensing of Dr Clare’s Blended Herbs

Special | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | ALL

C |

|---|

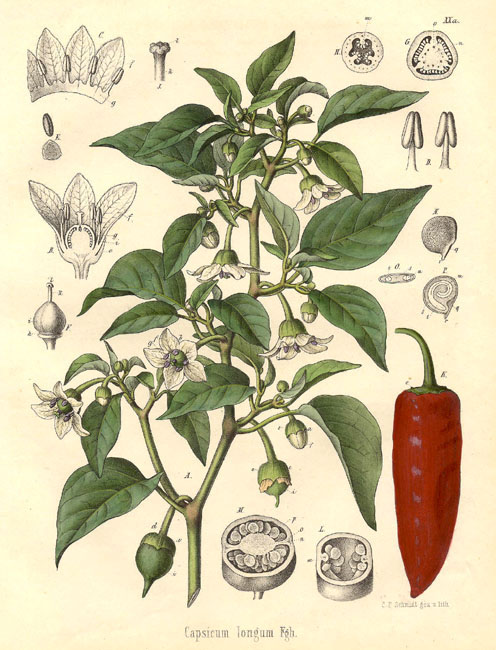

Cayenne

African Bird Pepper, African Chillies, African Pepper, Aji, Bird Pepper, Capsaicin, Capsaïcine, Cayenne, Cayenne Pepper, Chili, Chili Pepper, Chilli, Chillies, Cis-capsaicin, Civamide, Garden Pepper, Goat's Pod, Grains of Paradise, Green Chili Pepper, Green Pepper, Hot Pepper, Hungarian Pepper, Ici Fructus, Katuvira, Lal Mirchi, Louisiana Long Pepper, Louisiana Sport Pepper, Mexican Chilies, Mirchi, Oleoresin Capsicum, Paprika, Paprika de Hongrie, Pili-pili, Piment de Cayenne, Piment Enragé, Piment Fort, Piment-oiseau, Pimento, Poivre de Cayenne, Poivre de Zanzibar, Poivre Rouge, Red Pepper, Sweet Pepper, Tabasco Pepper, Trans-capsaicin, Zanzibar Pepper, Zucapsaicin, Zucapsaïcine. CAUTION: See separate listings for Grains of Paradise and Indian Long Pepper.Scientific Name:Capsicum frutescens; Capsicum annuum; Capsicum chinense; Capsicum baccatum; Capsicum pubescens; Capsicum minimum; and other Capsicum species. People Use This For: Orally, capsicum is used for dyspepsia, flatulence, colic, diarrhea, cramps, toothache, poor circulation, excessive blood clotting, seasickness, swallowing dysfunction, alcoholism, malaria, fever, hyperlipidemia, and preventing heart disease. Intranasally, capsicum is used for allergic rhinitis, perennial rhinitis, migraine headache, cluster headache, sinonasal polyposis, and sinusitis Safety: LIKELY SAFE ...when used orally in amounts typically found in food. Capsicum has Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) status in the US (5). ...when used topically and appropriately. The active capsicum constituent capsaicin used in topical preparations is an FDA-approved over-the-counter product (1). Effectiveness: Pain. Several clinical studies show that applying 0.25% to 0.75% capsaicin cream topically temporarily relieves chronic pain from rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, psoriasis, and neuralgias including shingles and diabetic neuropathy (13, 47). The active capsicum constituent capsaicin, used in topical preparations, is FDA-approved for these uses (1). Back pain. Some evidence shows that applying a capsicum-containing plaster to back can significantly reduce low-back pain compared to placebo (44, 45. 46). Prurigo nodularis. Applying a cream containing 0.025% to 0.3% of the active capsicum constituent capsaicin 4-6 times daily seems to relieve burning sensations, erythema, pruritus, and healing of skin lesions over a period of 2 weeks to 33 months. Symptoms, however, may return after discontinuation of therapy (48). HIV-associated peripheral neuropathy. Applying capsaicin topically does not seem to relieve symptoms of HIV-associated peripheral neuropathy (4). INSUFFICIENT RELIABLE EVIDENCE to RATE Allergic rhinitis. Preliminary research suggests that intranasal treatment with cotton wads soaked in capsaicin applied for 15 minutes and repeated over two days might reduce the severity of experimentally induced allergic rhinitis. Severity of symptoms seems to be decreased for up to two months after capsaicin treatment (30). However, contradictory evidence suggests that patients with allergic rhinitis caused by house dust mites do not have significantly improved symptoms after using a capsaicin solution providing 0.15 mg/dose for up to 7 doses over a 14-day period (42). Swallowing dysfunction. Preliminary evidence suggests that elderly patients at risk for aspiration pneumonia due to swallowing dysfunction have improved swallowing reflexes after dissolving a capsaicin-containing lozenge in their mouth before each meal (27).

Mechanism of Action:

The applicable part of capsicum is the fruit. Capsicum contains the constituent capsaicin, which makes it taste hot. Capsicum powder has been reported to prevent radiation-induced damage to bacterial DNA and thereby protect certain bacteria (Escherichia coli, Bacillus megaterium, and Bacillus pumilus spores) from gamma irradiation, which is used to preserve some foods (6).

Adverse Reactions: Orally, capsicum can cause upper abdominal discomfort including fullness, gas, bloating, nausea, epigastric pain and burning, diarrhea, and belching (12, 22). Sweating and flushing of the head and neck, lacrimation, headache, faintness, and rhinorrhea have also been reported (8, 22). Excessive amounts of capsaicin can lead to gastroenteritis and hepatic necrosis (13). There are also reports of dermatitis in breast-fed infants whose mothers' food is heavily spiced with capsicum (2). Capsicum can also decrease blood coagulation (9). Capsicum oleoresin, an oily extract in pepper self-defense sprays, causes intense eye pain. It can also cause erythema, blepharospasm, tearing, shortness of breath, and blurred vision. In rare cases, corneal abrasions have occurred (20, 21).

Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: ANTICOAGULANT/ANTIPLATELET HERBS AND SUPPLEMENTS: Concomitant use of herbs and supplements that affect platelet aggregation could theoretically increase the risk of bleeding in some people. Some of these herbs include angelica, clove, danshen, garlic, ginger, ginkgo, Panax ginseng, and others. Interactions with Drugs:

ACE INHIBITORS (ACEIs) <<interacts with>> CAPSICUM Interaction Rating = Minor Be watchful with this combination. Severity = Mild • Occurrence = Unlikely • Level of Evidence = D

There is one case report of a topically applied cream containing capsaicin contributing to the cough reflex in a patient using an ACE-inhibitor (26). (12414). But it is unclear if this interaction is clinically significant.

ANTICOAGULANT/ANTIPLATELET DRUGS <<interacts with>> CAPSICUM Interaction Rating = Moderate Be cautious with this combination. Severity = High • Occurrence = Possible • Level of Evidence = D

Theoretically, capsicum might increase the effects and adverse effects of antiplatelet drugs (15, 16). COCAINE <<interacts with>> CAPSICUM Interaction Rating = Moderate Be cautious with this combination. Severity = High • Occurrence = Possible • Level of Evidence = D Theoretically, concomitant use of capsicum (including exposure to the capsicum in pepper spray) and cocaine might increase cocaine effects and the risk of adverse effects, including death (3). THEOPHYLLINE <<interacts with>> CAPSICUMInteraction Rating = Moderate Be cautious with this combination. Severity = Moderate • Occurrence = Possible • Level of Evidence = D

Theoretically, oral administration of capsicum before or at the same time as theophylline might enhance theophylline absorption (14). Interactions with Foods:None known.Interactions with Lab Tests:BLEEDING TIME: Capsicum has led to increased fibrinolytic activity and may lead to prolonged times in coagulation studies (9).Interactions with Diseases or Conditions:DAMAGED SKIN: Capsicum is contraindicated in situations involving injured skin. Do not apply capsicum if the skin is open. | |

Chamomile

Blue Chamomile, Camomilla, Camomille, Camomille Allemande, Chamomilla, Echte Kamille, Feldkamille, Fleur de Camomile, Hungarian Chamomile, Kamillen, Kleine Kamille, Manzanilla, Manzanilla Alemana, Matricaire, Matricariae Flos, Pin Heads, Sweet False Chamomile, True Chamomile, Wild Chamomile. Scientific Name: Matricaria recutita, synonyms Chamomilla recutita, Matricaria chamomilla. Family: Asteraceae/Compositae. People Use This For: Orally, German chamomile is used for flatulence, travel sickness, nasal mucous membrane inflammation, allergic rhinitis, nervous diarrhea, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), fibromyalgia, restlessness, and insomnia. It is also used for gastrointestinal (GI) spasms, colic, inflammatory diseases of the GI tract, GI ulcers associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and alcohol consumption, and as an antispasmodic for menstrual cramps. Topically, German chamomile is used for hemorrhoids; mastitis; leg ulcers; skin, anogenital, and mucous membrane inflammation; and bacterial skin diseases, including those of the mouth and gums. It is also used topically for treating or preventing chemotherapy- or radiation-induced oral mucositis. As an inhalant, German chamomile is used to treat inflammation and irritation of the respiratory tract. In foods and beverages, German chamomile is used as flavor components. In manufacturing, German chamomile is used in cosmetics, soaps, and mouthwashes. Safety: No concerns regarding safety, available studies validate this statement, when used orally in amounts commonly found in foods. German chamomile has Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status in the US.1 No concerns regarding safetywhen used orally, short-term. There is some evidence that German chamomile can be used safely for up to 8 weeks.2,3,4 The long-term safety of German chamomile in medicinal doses is unknown, when used topically; avoid applying it near the eyes.5 Children: No concerns regarding safety when used orally and appropriately, short-term. Preliminary clinical research also suggests that a specific multi-ingredient product containing fennel 164 mg, lemon balm 97 mg, and German SourceURL:file://localhost/Users/ruthruane/Downloads/Herbal%20Medicine-Newest.doc chamomile 178 mg (ColiMil, Milte Italia SPA) is safe in infants when used for up to a week.6 Pregnancy and Lactation: Insufficient reliable information available; avoid using.

Effectiveness: POSSIBLY EFFECTIVE Colic. A clinical trial shows that breast-fed infants with colic who are given a specific multi-ingredient product containing fennel 164 mg, lemon balm 97 mg, and German chamomile 178 mg (ColiMil, Milte Italia SPA) twice daily for a week have reduced crying times compared to placebo.6

Dyspepsia. A specific combination product containing German chamomile (Iberogast, Medical Futures, Inc) seems to improve symptoms of dyspepsia. The combination includes German chamomile plus peppermint leaf, clown's mustard plant, caraway, licorice, milk thistle, celandine, angelica, and lemon balm.7,3 A meta-analysis of studies using this combination product suggests that taking 1 mL orally three times daily over a period of 4 weeks significantly reduces severity of acid reflux, epigastric pain, cramping, nausea, and vomiting compared to placebo.8

Oral mucositis. Using a German chamomile oral rinse (Kamillosan Liquidum) might help prevent or treat mucositis induced by radiation therapy and some types of chemotherapy.2 German chamomile oral rinse seems to prevent or treat mucositis secondary to radiation therapy and some types of chemotherapy including asparaginase (Elspar), cisplatin (CDDP, Platinol-AQ), cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan, Neosar), daunorubicin (DaunoXome), doxorubicin (Adriamycin, Rubex), etoposide (VP-16, Etopophos, VePesid, Toposar), hydroxyurea (Hydrea), mercaptopurine (6-MP, Purinethol), methotrexate (MTX, Rheumatrex), procarbazine (MIH, Mutlane), and vincristine (VCR, Oncovin, Vincasar) (2). However, the rinse doesn't seem to be better than placebo for preventing fluorouracil (5-FU)-induced oral mucositis.9

POSSIBLY INEFFECTIVE Dermatitis. Applying German chamomile cream topically does not seem to prevent dermatitis induced by cancer radiation therapy.10

Mechanism of Action: The applicable part of German chamomile is the flowerhead. Active constituents of German chamomile include quercetin, apigenin, and coumarins, and the essential oils.5

German chamomile might have anti-inflammatory effects. Preliminary research suggests it can inhibit the pro inflammatory enzymes. Other constituents may inhibit histamine related to allergies,5,4 The constituent(s) responsible for the sedative activity of German chamomile are unclear. Preliminary research suggests that extracts of German chamomile might inhibit morphine dependence and withdrawal.11 Other preliminary research suggests that German chamomile flower extract taken orally might have an antipruritic effect.12 Preliminary research suggests that German chamomile blocks slow wave activity in the small intestine, which could slow peristaltic movement.13

Adverse Reactions: Orally, German chamomile tea can cause allergic reactions including severe reactions in some patients.14

Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: HERBS AND SUPPLEMENTS WITH SEDATIVE PROPERTIES: Theoretically, concomitant use with herbs that have sedative properties might have additive effects which needs to be taken into account.5,16 Interactions with Drugs: Benzodiazepines: Consult a Medical Herbalist CNS Depressants: Consult a Medical Herbalist Warfarin (Coumadin): Consult a Medical Herbalist Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: Creatinine: Chronic ingestion of German chamomile for two 2 weeks can reduce urinary creatinine output. This effect may be prolonged for up to two weeks after discontinuing German chamomile. The mechanism for this effect is unclear.4 Interactions with Diseases or Conditions: Surgery: Avoid from 2 weeks prior to elective surgery. Dosage/Administration: Oral: For dyspepsia, a specific combination product containing German chamomile (Iberogast, Medical Futures, Inc) and several other herbs has been used in a dose of 1 mL three times daily.7,3,8 For colic in infants, a specific multi-ingredient product containing fennel 164 mg, lemon balm 97 mg, and German chamomile 178 mg (ColiMil, Milte Italia SPA) twice daily for a week has been used.6 Topical: For chemotherapy- or radiation-induced oral mucositis, an oral rinse made with 10-15 drops of German chamomile liquid extract in 100 mL warm water has been used three times daily.2 Comments: German chamomile is an annual herb found throughout Europe and in portions of Asia. German chamomile has a mild apple-like scent. The name "chamomile" is Greek for "Earth apple." Specific References: CHAMOMILE 1. FDA. Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Office of Premarket Approval, EAFUS: A food additive database. Available at: vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/eafus.html. 2. Carl W, Emrich LS. Management of oral mucositis during local radiation and systemic chemotherapy: a study of 98 patients. J Prosthet Dent 1991;66:361-9. 3. Madisch A, Holtmann G, Mayr G, et al. Treatment of functional dyspepsia with a herbal preparation. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Digestion 2004;69:45-52. 4. Wang Y, Tang H, Nicholson JK, et al. A metabonomic strategy for the detection of the metabolic effects of chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) ingestion. J Agric Food Chem 2005;53:191-6. 5. Hormann HP, Korting HC. Evidence for the efficacy and safety of topical herbal drugs in dermatology: part I: anti-inflammatory agents. Phytomedicine 1994;1:161-71. 6. Savino F, Cresi F, Castagno E, et al. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of a standardized extract of Matricariae recutita, Foeniculum vulgare and Melissa officinalis (ColiMil) in the treatment of breastfed colicky infants. Phytother Res 2005;19:335-40. 7. Holtmann G, Madisch A, Juergen H, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial on the effects of an herbal preparation in patients with functional dyspepsia [Abstract]. Ann Mtg Digestive Disease Week 1999 May. 8. Melzer J, Rosch W, Reichling J, et al. Meta-analysis: phytotherapy of functional dyspepsia with the herbal drug preparation STW 5 (Iberogast). Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20:1279-87. 9. Fidler P, Loprinzi CL, O'Fallon JR, et al. Prospective evaluation of a chamomile mouthwash for prevention of 5-FU-induced oral mucositis. Cancer 1996;77:522-5. 10. Maiche AG, Grohn P, Maki-Hokkonen H. Effect of chamomile cream and almond ointment on acute radiation skin reaction. Acta Oncol 1991;30:395-6. 11. Gomaa A, Hashem T, Mohamed M, Ashry E. Matricaria chamomilla extract inhibits both development of morphine dependence and expression of abstinence syndrome in rats. J Pharmacol Sci 2003;92:50-5. 12. Kobayashi Y, Nakano Y, Inayama K, et al. Dietary intake of the flower extracts of German chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) inhibited compound 48/80-induced itch-scratch responses in mice. Phytomedicine 2003;10:657-64. 13. Storr M, Sibaev A, Weiser D, et al. Herbal extracts modulate the amplitude and frequency of slow waves in circular smooth muscle of mouse small intestine. Digestion 2004;70:257-64. 14. Subiza J, Subiza JL, Hinojosa M, et al. Anaphylactic reaction after the ingestion of chamomile tea; a study of cross-reactivity with other composite pollens. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1989;84:353-8. 15. Viola H, Wasowski C, Levi de Stein M, et al. Apigenin, a component of Matricaria recutita flowers, is a central benzodiazepine receptors-ligand with anxiolytic effects. Planta Med 1995;61:213-6. 16. Avallone R, Zanoli P, Puia G, et al. Pharmacological profile of apigenin, a flavonoid isolated from Matricaria chamomilla. Biochem Pharmacol 2000;59:1387-94. | |

Cinnamon

Also Known As: Cassia Cinnamon, Canela de Cassia, Canela Molida, Canelle, Cannelle Scientific Name: Cinnamomum aromaticum, synonyms Cinnamomum cassia, and Cinnamomum People Use This For: Orally, cassia cinnamon is used for type 2 diabetes, gas (flatulence), muscle and Safety: LIKELY SAFE ...when used orally and appropriately. Cassia cinnamon has been Effectiveness: INSUFFICIENT RELIABLE EVIDENCE to RATE Diabetes. There is contradictory evidence about the effectiveness of cassia Mechanism of Action: The applicable parts of cassia cinnamon are the bark and flower. Adverse Reactions: Orally, cassia cinnamon appears to be well-tolerated. No significant side effects Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: HEPATOTOXIC HERBS AND SUPPLEMENTS: There is some concern that Interactions with Drugs: ANTIDIABETES DRUGS <<interacts with>> CASSIA CINNAMON Interaction Rating = Moderate Be cautious with this combination. Cassia cinnamon may lower blood glucose levels, and have additive effects in HEPATOTOXIC DRUGS <<interacts with>> CASSIA CINNAMON Interaction Rating = Moderate Be cautious with this combination. Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: BLOOD GLUCOSE: Cassia cinnamon might lower blood glucose levels and test Interactions with Diseases or Conditions: DIABETES: Cassia cinnamon might lower blood glucose in patients with type Dosage/Administration: ORAL: For type 1 or type 2 diabetes, 1 to 6 grams (1 teaspoon = 4.75 grams) of cassia cinnamon daily for up to 4 months have been used. (8, 13, 18, 19). Editor's Comments: There are a lot of different types of cinnamon. Cinnamomum verum (Ceylon Specific References: Cinnamon 1. lectronic Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21. Part 182 - 2. Lee HS, Ahn YJ. Growth-Inhibiting Effects of Cinnamomum cassia Bark- 3. Koh WS, Yoon SY, Kwon BM, et al. Cinnamaldehyde inhibits lymphocyte 4. Kwon BM, Lee SH, Choi SU, et al. Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity of 5.Anderson RA, Broadhurst CL, Polansky MM, et al. Isolation and 6. Jarvill-Taylor KJ, Anderson RA, Graves DJ. A hydroxychalcone derived from 7. Imparl-Radosevich J, Deas S, Polansky MM, et al. Regulation of PTP-1 and 8. 11347 Khan A, Safdar M, Ali Khan M, et al. Cinnamon improves glucose and 9. De Benito V, Alzaga R. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis from cassia 10.Drake TE, Maibach HI. Allergic contact dermatitis and stomatitis caused by a 11.Onderoglu S, Sozer S, Erbil KM, et al. The evaluation of long-term effcts 12. 3238 13. 14. ress release. Cinnamon capsules to reduce blood sugar are medicinal 15.Miller KG, Poole CF, Pawloski TMP. Classification of the botanical origin 16.He ZD, Qiao CF, Han QB, et al. Authentication and quantitative analysis on 17.Felter SP, Vassallo JD, Carlton BD, Daston GP. A safety assessment of 18.Baker WL, Gutierrez-Williams G, White CM, et al. Effect of cinnamon on 19. Crawford P. Effectiveness of cinnamon for lowering hemoglobin A1C in 20. Blevins SM, Leyva MJ, Brown J, et al. Effect of cinnamon on glucose and lipid | |

Cleavers

Bedstraw, Catchweed, Cleavers, Gallium, Goose Grass, Gosling Weed, Robin-Run-in-the-Grass, Scratchweed, Stick-a-Back, Sticky Willy. Scientific Name: Galium aparine. Family: Rubiaceae. People Use This For: Clivers is used as a diuretic, a mild astringent, for dysuria, lymphadenitis, psoriasis, and specifically for enlarged lymph nodes. Safety: No concerns regarding safety when used orally and appropriately.13 There is no documented toxicity.14 Pregnancy and Lactation: Refer to a Medical Herbalist. Effectiveness: There is insufficient scientific information available about the effectiveness of clivers. Mechanism of Action: The applicable parts of clivers are the dried or fresh above ground parts. Cleavers contain tannins, which are reported to have astringent properties.14 Adverse Reactions: None reported. Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: None known. Interactions with Drugs: None known. Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: None known. Dosage/Administration: Dr Clare’s Blends: 1gm per day. Oral: Typical doses are 2-4 grams dried above ground parts three times daily, or one cup tea (steep 2-4 grams herb in 150 mL boiling water 5-10 minutes, strain) three times daily.14 Liquid extract (1:1 in 25% alcohol) 2-4 mL three times daily.14 Spedific References: CLIVERS 13. McGuffin M, Hobbs C, Upton R, Goldberg A, eds. American Herbal Products Association's Botanical Safety Handbook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, LLC 1997. 14. Newall CA, Anderson LA, Philpson JD. Herbal Medicine: A Guide for Healthcare Professionals. London, UK: The Pharmaceutical Press, 1996. | |

CORE REFERENCES

R5. Grases, F., March, J. G., Ramis, M. & Costa-Bauzá, A. (1993) The influence of Zea mays on urinary risk factors for kidney stones in rats.

| |

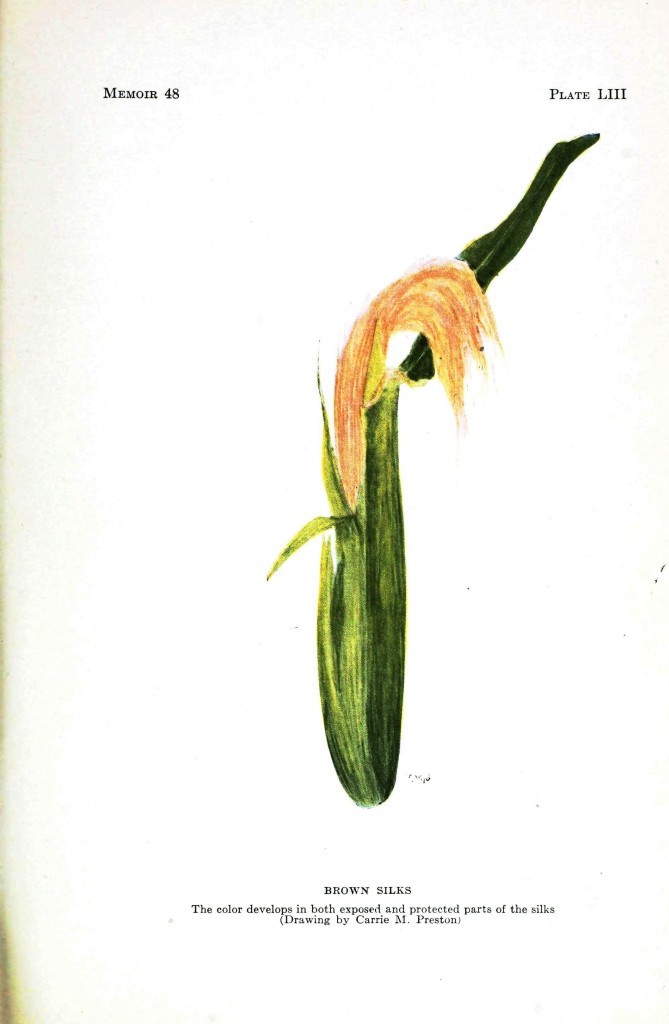

Cornsilk

Indian Corn, Yu Mi Xiu, Zea. Scientific Name: Zea mays. Family: Poaceae/Gramineae. People Use This For: Orally, corn silk is used for cystitis, urethritis, bedwetting, inflammation of the prostate, acute and chronic inflammation of the urinary system. Safety: No concerns regading safety, available studies validate this statement, when used orally in amounts commonly found in foods. Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status in the US.6 No concerns regarding safety when used orally and appropriately in medicinal amounts.7 Pregnancy and Lactation: Refer to a Medical Herbalist Effectiveness: There is not enough scientific information available to comment about the effectiveness of corn silk. Mechanism of Action: Corn silk contains tannins, which are astringent, and cryptoxanthin, which has vitamin A activity.8 Diuretic. Demulcent (mucilagenous). Choleretic (promotes bile flow). The diuretic and choleretic action has been demonstrated in animal studies.R5 In China it is used for Hepato-Biliary Disease.R6,R7 Adverse Reactions: None. Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: Herbs and Supplements with Hypotensive Effects: Corn silk is thought to have hypotensive effects, may have an additive effect with blood pressure lowering agents. Interactions with Drugs: Antidiabetes Drugs: Theoretically, because some evidence suggests corn silk can reduce blood glucose levels, excessive amounts might interfere with diabetes therapy.R1 pp.222 Diuretic Drugs: Additive Effect.R4 pp.192,204,215 Lithium: Because of Diuretic effect. Warfarin (Coumadin): Corn silk contains vitamin K. Individuals taking warfarin should consume a consistent daily amount to maintain consistent anticoagulation.9 Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: None known. Interactions with Diseases or Conditions: None within normal dose range. Dosage/Administration: Oral: 4-8 grams dried style/stigma three times daily, or one cup tea (steep 0.5 grams dried corn silk in 150 mL boiling water 5-10 minutes, strain) several times daily.8,10 Liquid extract of maize stigmas, 4-8 mL.8 Tincture (1:5 in 25% alcohol), 5-15 mL three times daily. 8 Syrup of maize stigmas, 8-15 mL.8 Dr Clare’s Comments: Corn silk is the silky threads that surround the ear of sweetcorn. It is one on the few herbs that are more effective dried, probably because they have such a high water content it would take a lot of them to make an effective fresh infusion. It would be nice to think that Corn Silk would ‘treat’ high blood pressure/diabetes however it is likely to be helpful in the way an extra portion of fruit or vegetables are helpful. It will not reduce a normal blood sugar or a normal Blood Pressure in my experience. Nor has it been reported, these are theoretical considerations. Specific References: CORN SILK 6. FDA. Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Office of Premarket Approval, EAFUS: A food additive database. Available at: vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/eafus.html. 7. McGuffin M, Hobbs C, Upton R, Goldberg A, eds. American Herbal Products Association's Botanical Safety Handbook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, LLC 1997. 8. Newall CA, Anderson LA, Philpson JD. Herbal Medicine: A Guide for Healthcare Professionals. London, UK: The Pharmaceutical Press, 1996. 9. Brinker F. Herb Contraindications and Drug Interactions. 2nd ed. Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications, 1998. Wichtl MW. Herbal Drugs and Phytopharmaceuticals. Ed. N.M. Bisset. 10. Stuttgart: Medpharm GmbH Scientific Publishers, 1994 | |

Couchgrass

Agropyron, Coughgrass, Cutch, Dog Grass. Scientific Name: Agropyron repens. Family: Poaceae/Gramineae. People Use This For: It is used orally to treat cystitis, urethritis, prostatitis, benign prostatic hypertrophy and kidney stones. Safety: No concerns regarding safety, available studies validate this statement, when consumed in amounts commonly found in foods.11 Pregnancy and Lactation: Refer to a Medical Herbalist. Effectiveness: Not enough scientific information gather to offer a comment. Mechanism of Action: Diuretic.R8 pp.18,R1 pp.222 Adverse Reactions: None known Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: None known. Interactions with Drugs: None known. Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: None known. Interactions with Diseases or Conditions: None known. Dosage/Administration: Oral: For treating ulcerative colitis, 100 mL of wheatgrass juice daily for 1 month has been used.12 DrClare’s Blends: Specific References: COUCHGRASS 11. Rauma AL, Nenonen M, Helve T, et al. Effect of a strict vegan diet on energy and nutrient intakes by Finnish rheumatoid patients. Eur J Clin Nutr 1993;47:747-9. 12. Ben-Arye E, Golden E, Wengrower D, et al. Wheat grass juice in the treatment of active distal ulcerative colitis a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002;4:444-9. | |

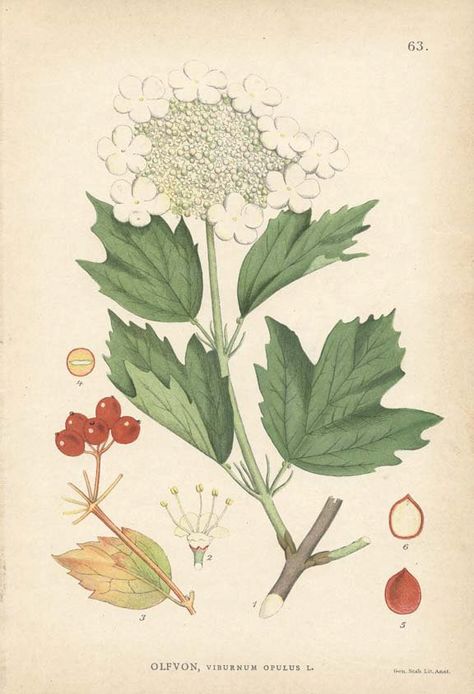

Cramp Bark

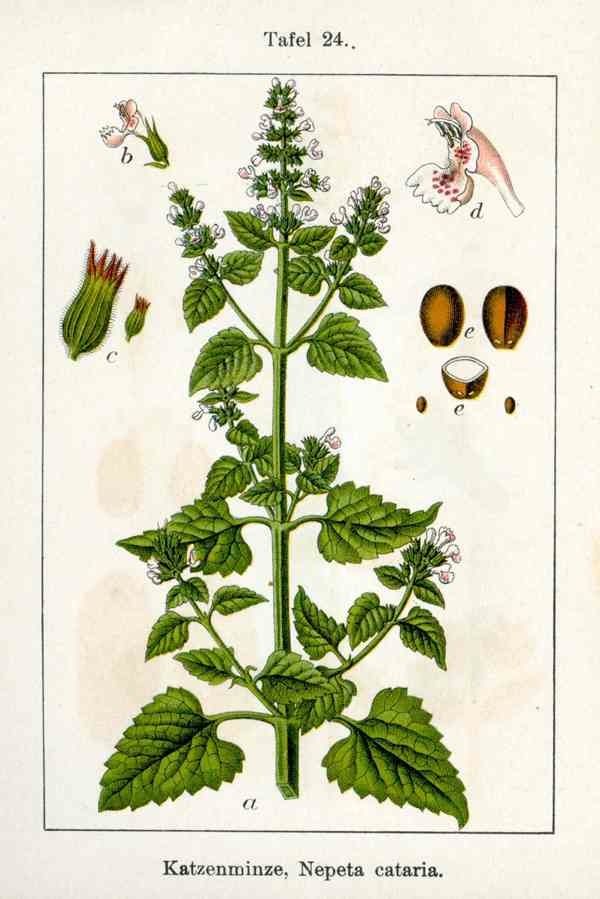

Also known as: Common Guelder-Rose, Cranberry Bush. Scientific Name: Viburnum opulus. Botanical Family: Adoxaceae/Viburnaceae (formerly known as Caprifoliaceae). Part used: Bark and root bark.

Traditional Use. Cramp bark has antispasmodic (relieves muscle spasms), anti-inflammatory (relieves inflammation), nervine (calms and soothes the nerves), hypotensive (lowers blood pressure), astringent (causes local contraction), emmenagogic (induces menstruation ), and sedative (reduces activity and excitement) properties.

Safety. There are no reports of safety concerns regarding Cramp Bark.

Pregnancy: Refer to a Medical Herbalist. Breastfeeding: Refer to a Medical Herbalist. Constituents Hydroquinines; arbutin, methylarbutin and traces of free hydroquinone. Sesquiterpene dialdehyde fraction; viopudiol. Coumarins; such as scopoletinans, esculatin. Triterpinoids; including oleanic acid and ursolic acid derivatives. Iridoid glysoside esters.

Scientific evidence. No clinical research has been done. Mechanism of action. At least two active constituents have been identified, scopoletin and viopudial. These constituents appear to have smooth muscle antispasmodic effects in vitro. Viopudial appears to have cholinergic effects by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase. The effect opposes the dominence of the sympathetic nervous system and relaxes the tone in smooth muscles. There is evidence of anti-inflammatory effects.

One study showed that the administration of viopudial, a Viburnum opulus component, produces slowing of the heart rate, lowering of blood pressure, and some decrease in contractility of heart muscle. This action is by balancing the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system tone in the body. Experimental evidence indicates that viopudial's mechanism of action is partly due to its effects on cholinesterase. In vitro demonstrations of a competitive inhibitory effect on both acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase showed viopudial to be relatively weak when compared to the known potent inhibitor, physostigmine. Additional mechanistic effects, such as a direct musculotrophic action, may also be responsible for the overall activity. 8 One animal study shows that proanthocyanidin constituents of Viburnum opulus exert a potent gastro-duodenoprotective effect by increasing nitrous oxide in the tissues, suppressing lipid peroxidation and mobilizing antioxidant activity and changes in the gastroduodenal mucosa of rat.7 Other studies show that Viburnum opulus exhibits anti-oxidant effects.9

Adverse reactions. None reported.

Possible interactions with herbs and supplements. None known.

Possible interactions with drugs. None known.

Possible interactions with foods. None known.

Interactions with laboratory tests. None known.

Effects on diseases or conditions. None known.

Dosage. Recommended dose: 3-10mls per day 1:5 tincture 30% alcohol. Decoction: range from ½ to 6 tsps. per day. Powder/capsule: range from 1-4gms per day. Raw herb: 2-4gms per day.R8 pp.230 Liquid extract: 2-8ml/day.

The recommended dose of Dr Clare’s Joint Support Blend provides 3mls per day of 1:3 Tincture in 15mls daily, at a dose of 5mls three times a day. This is equivalent to 375-750mgs per day.

References. 1. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) June 1972 vol. 140 no. 2 457-461 Viopudial, a Hypotensive and Smooth Muscle Antispasmodic from Viburnum opulus.John A. Nicholson,Thomas D. Darby, Charles H. Jarboe

2. Charles H. Jarboe , Karimullah A. Zirvi , John A. Nicholson , Charlotte M. Schmidt. Scopoletin, an Antispasmodic Component of Viburnum opulus and prunifolium J. Med. Chem., 1967, 10 (3), pp 488–489

3. Antioxidant properties of Viburnum opulus and Viburnum lantana growing in Turkey. Dr Mehmet Levent Altun, Gülçin Saltan Çitoğlu, Betül, Sever Yilmaz and Tülay Çoban International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 2008, Vol. 59, No. 3 , Pages 175-180

4. Antinociceptive and Anti-inflammatory Activities of Viburnum lantana. Pharmaceutical Biology2007, Vol. 45, No. 3 , Pages 241-245 B. Sever Yilmaz, G Saltan Citoglu, M.L. Altun and H. Ozbek

5. Zeng LJ, Xing JB, Li P. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica [2000, 25(3):184-188]

6. Ilkay Erdogan-Orhan, Mehmet Levent Altun, Betül Sever-Yilmaz, and Gülçin Saltan. Anti-Acetylcholinesterase and Antioxidant Assets of the Major Components (Salicin, Amentoflavone, and Chlorogenic Acid) and the Extracts of Viburnum opulus and Viburnum lantana and Their Total Phenol and Flavonoid Contents Journal of Medicinal Food. April 2011, 14(4): 434-440.

7. Zayachkivska OS1, Gzhegotsky MR, Terletska OI, Lutsyk DA, Yaschenko AM, Dzhura OR. Influence of Viburnum opulus proanthocyanidins on stress-induced gastrointestinal mucosal damage. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006 Nov;57 Suppl 5:155-67.

8. Viopudial, a hypotensive and smooth muscle antispasmodic from Viburnum opulus. J A Nicholson, T D Darby, C H Jarboe Proceedings of The Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine 07/1972; 140(2):457-61.

9. Andreeva T.I, Komarova E.N, Yusubov M. S, Korotkova E.I. Antioxidant activity of cranberry tree (Viburnum Opulus L.) bark extract. Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal 10-2004, Volume 38, Issue 10, pp 548-550

| |

Also Known As:

Also Known As: Also Known As:

Also Known As: Also Known As:

Also Known As:

Also Known As:

Also Known As: Also Known As:

Also Known As: Also Known As:

Also Known As: Cramp Bark

Cramp Bark