Dr Clare Materia Medica

Introduction to the Dispensing of Dr Clare’s Blended Herbs

Special | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | ALL

A |

|---|

AshwagandaAlso Known As: Withania. Scientific Name: Withania somnifera. Family: Solanaceae. People Use This For: Ashwagandha is traditionally used for arthritis, anxiety, insomnia, tumors, tuberculosis, and chronic liver disease. Ashwagandha is also used as an "adaptogen" to increase resistance to environmental stress, and as a general tonic. It is also used for immunomodulatory effects, improving cognitive function, decreasing inflammation, preventing the effects of aging, for emaciation, infertility in men and women, menstrual disorders, fibromyalgia, and hiccups. It is also used orally as an aphrodisiac. Safety: Possibly safe when used orally and appropriately, short-term.17,18 Pregnancy and Breastfeeding: Insufficient scientific information available, consult a medical herbalist. Effectiveness: There is insufficient scientific information available to comment. Mechanism of Action: The applicable parts of ashwagandha are the root and berry. Ashwagandha contains several active constituents including alkaloids, steroidal lactones, and saponins.19,18. Animal model research suggests that ashwagandha has a variety of pharmacological effects including pain relief, lowering temperature, reducing anxiety, inflammatory, and antioxidant effects.17,20,21,19,18 , sedative, blood pressure lowering, anti-immunomodulatory. Some researchers think ashwagandha has a so-called "anti-stressor" effect. Preliminary increases of dopamine receptors in the corpus striatum of the brain. 17 It also appears to reduce stress-induced increases of plasma corticosterone, blood urea nitrogen, and blood lactic acid.18 Ashwagandha seems to have anxiolytic effects, possibly by acting as a gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) mimetic agent. Research suggests ashwagandha suppresses stress-induced anxiety. Ashwagandha and its constituents also seem to have modulating effects on the immune system. The withanolides and sitoindosides seem to cause a mobilization of phagocytosis, and lysosomal enzymes.18 Adverse Reactions: Ashwagandha is well tolerated. Interactions with Herbs & Supplements Herbs and Supplements with Sedative Properties: Theoretically, used with herbs that have sedative properties they may have an additive effect. This needs to be taken into account with the dosage. Interactions with Drugs: Benzodiazepines e.g.Valium, Xanax CNS Depressants: Theoretically, Ashwagandha's sedative effect may add to the effects of barbiturates (rarely prescribed now except for epilepsy), other sedatives, and drugs for anxiety,17 needed. Immunosuppressants; refer to medical herbalist Thyroid Hormone: Theoretically, ashwagandha might have additive effects when used with thyroid supplements. There is preliminary evidence that ashwagandha might boost thyroid hormone synthesis and/or secretion.17 Refer patients on medication to a well qualified Medical Herbalist. Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: Digoxin blood levels (heart medication). Interactions with Diseases or Conditions: Autoimmune effects.17,20,22,18 The modulating effects on the immune system can be helpful but should be prescribed by a Medical Herbalist. Diseases: Ashwagandha may have immunostimulant properties. Dosage/Administration: Dr Clare’s Blends: 1gm per day Oral: People typically use 1 to 6 grams daily of the whole herb in capsule or tea form.17 The tea is prepared by boiling ashwagandha roots in water for 15 minutes and cooled. The usual dose is 3 cups daily. Tincture or fluid extracts are dosed 2 to 4 mL 3 times per day. Topical: No typical dosage. Specific References: ASHWAGANDHA Upton R, ed. Ashwagandha Root (Withania somnifera): Analytical, quality control, and 17. therapuetic monograph. Santa Cruz, CA: American Herbal Pharmacopoeia 2000:1-25. 18. Mishra LC, Singh BB, Dagenais S. Scientific basis for the therapeutic use of Withania somnifera (ashwagandha): a review. Altern Med Rev 2000;5:334-46. 19. Bhattacharya SK, Satyan KS, Ghosal S. Antioxidant activity of glycowithanolides from Withania somnifera. Indian J Exp Biol 1997;35:236-9. 20. Davis L, Kuttan G. Effect of Withania somnifera on cyclophosphamide-induced urotoxicity. Cancer Lett 2000;148:9-17. 21. Archana R, Namasivayam A. Antistressor effect of Withania somnifera. J Ethnopharmacol 1999;64:91-3. 22. Davis L, Kuttan G. Suppressive effect of cyclophosphamide-induced toxicity by Withania somnifera extract in mice. J Ethnopharmacol | |

Astragalus

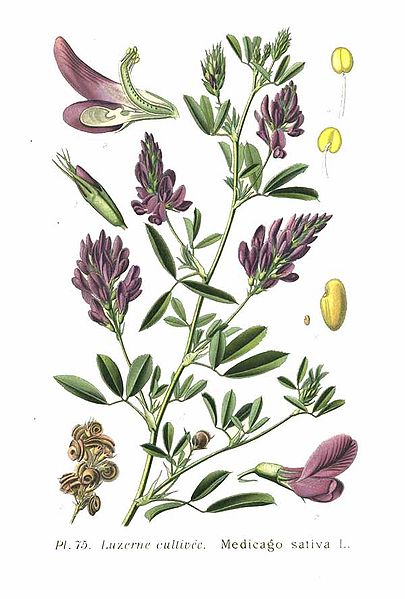

Also Known As: Astragali Membranaceus. Scientific Name:Astragalus membranaceus. Family: Fabaceae/Leguminosae or Papilionaceae. People Use This For: Astragalus is used for common cold, upper respiratory infections, allergic rhinitis, swine ‘flu, to strengthen and regulate the immune system, fibromyalgia, anemia, and HIV/AIDS, chronic fatigue syndrome, as an antibacterial, antiviral, tonic, liver protectant, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, as a diuretic, vasodilator, and as a hypotensive agent. Topically, astragalus is used as a vasodilator and to speed healing. Safety: No concerns regarding safety. Pregnancy and Breast Feeding: Refer to a Medical Herbalist. Effectiveness: Not enough scientific information available to comment. Allergic rhinitis: Preliminary clinical research shows that a specific astragalus root extract standardized to contain 34% polysaccharides twice daily for 3 to 6 weeks significantly improves symptoms such as runny nose, sneezing, and itching compared to placebo.1 Breast cancer: There is preliminary evidence that adjunctive use of astragalus in combination with glossy privet (Ligustrum lucidum) might increase survival rates in patients being treated conventionally for breast cancer.2 Common cold: There is preliminary evidence that long-term ingestion of astragalus might reduce the risk of catching the common cold.2 Hepatitis: There is preliminary evidence that intravenous use of astragalus might be beneficial for patients with chronic hepatitis.2 Mechanism of Action: The part used is the root. Astragalus contains a variety of active constituents including more than 34 saponins such as astragaloside, several flavonoids including isoflavones, pterocarpans, and isoflavans, polysaccharides, multiple trace minerals, amino acids, and coumarins.2,3 Astragalus has antioxidant effects. It inhibits free radical production, increases superoxide dismutase, and decreases lipid peroxidation.2,4 Astragalus is often promoted for its effects on the immune system, liver, and cardiovascular system. Astragalus seems to improve the immune response. In vitro, the polysaccharide constituents appear to bind and activate B cells and macrophages, but not T cells.5 Astragalus potentiates the effects of interferon, increases antibody levels of immunoglobulins in nasal secretions, and increases interleukin-2 levels.2,6,7 It also seems to improve the response of mononuclear cells and stimulate lymphocyte production.8 Additionally, there is preliminary evidence that astragalus extracts can restore or improve immune function in cases of immune deficiency.9,10 Astragalus seems to restore in vitro T-cell function which is suppressed in cancer patients.9,11 Astragalus also seems to have broad-spectrum in vitro antibiotic activity.2 There is interest in astragalus for increasing fertility. In vitro, astragalus appears to increase sperm motility.12 In individuals with chronic hepatitis, astragalus seems to improve liver function as demonstrated by improvement in serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase levels.2 Astragalus is also thought to cause vasodilation and increase cardiac output which might be beneficial in angina, congestive heart failure, and post-myocardial infarction.2 In animal models of heart failure, astragalus appears to increase myocardial and renal function, possibly due to diuretic and natriuretic effects.13 In animal models of coxsackie viral myocarditis, astragalus appears to reduce myocardial lesion size and viral titers.14 A pharmacokinetic evaluation in vitro and in a healthy human volunteer, suggests that astragalus flavonoids can be absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract. The major metabolites of the flavonoid constituents are glucuronides.15 These help with excretion of toxic substances. Adverse Reactions: Astragalus root is well-tolerated. Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: None known. Interactions with Drugs: Cyclophosphamide, Immunosuppressants, Lithium Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: None known. Interactions with Diseases or Conditions: Autoimmune Diseases: Refer to Medical Herbalist Dosage/Administration: Dr Clare’s Blends: 3ml of 1:3 tincture/day = 1gm per day. Oral: For allergic rhinitis, a specific astragalus root extract standardized to contain 34% polysaccharides (Lectranal) 160 mg twice daily has been used.1 For prevention of the common cold, 4-7 grams per day is commonly used.2 Traditionally, astragalus powder 1-30 grams per day is used.16,2 In some cases, people have used astragalus powder 30-54 grams per day.2 However, this should be avoided because some research suggests that doses greater than 28 grams per day offers no additional benefit and might even cause immune suppression.3 Astragalus decoction 0.5-1 L per day (maximum of 120 grams of whole root per liter of water) has been used.2 As a soup, mix 30 grams in 3.5 L of soup and simmer with other food ingredients.2 Topical: No typical dosage. Specific References: ASTRAGALUS Matkovic Z, Zivkovic V, Korica M, et al. Efficacy and safety of Astragalus membranaceus in 1. the treatment of patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Phytother Res 2010;18:175-81. 2. Upton R, ed. Astragalus Root: Analytical, quality control, and therapeutic monograph. Santa Cruz, CA: American Herbal Pharmacopoeia. 1999:1-19. 3. McCulloch M, See C, Shu XJ, et al. Astragalus-based Chinese herbs and platinum-based chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Clin Oncol 2006;18:419-30. Hong CY, Lo YC, Tan FC, et al. Astragalus membranaceus and Polygonum multiflorum 4. protect rat heart mitochondria against lipid peroxidation. Am J Chin Med 1994;22:57-70. 5. Shao BM, Xu W, Dai H, et al. A study on the immune receptors for polysaccharides from the roots of Astragalus membranaceus, a Chinese medicinal herb. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004;320:1103-11. 6. Qun L, Luo Q, Zhang ZY, et al. Effects of astragalus on IL-2/IL-2R system in patients with maintained hemodialysis. Clin Nephrol 1999;46:333-4. 7. Hou YD, Ma GL, Wu SH, et al. Effect of Radix Astragali seu Hedysari on the interferon system. Chin Med J (Engl) 1981;94:29-34. Sun Y, Hersh EM, Lee SL, et al. Preliminary observations on the effects of the Chinese 8. medicinal herbs Astragalus membranaceus and Ligustrum lucidum on lymphocyte blastogenic responses. J Biol Response Mod 1983;2:227-31. Sun Y, Hersh EM, Talpaz M, et al. Immune restoration and/or augmentation of local graft 9. versus host reaction by traditional Chinese medicinal herbs. Cancer 1983;46:70-3. 10. Chu DT, Wong WL, Mavligit GM. Immunotherapy with Chinese medicinal herbs. II. Reversal of cyclophosphamide-induced immune suppression by administration of fractionated Astragalus membranaceus in vivo. J Clin Lab Immunol 1988;19:125-9. 11. Chu DT, Wong WL, Mavligit GM. Immunotherapy with Chinese medicinal herbs. I. Immune restoration of local xenogeneic graft-versus-host reaction in cancer patients by fractionated Astragalus membranaceus in vitro. J Clin Lab Immunol 1988;19:119-17. 12. Hong CY, Ku J, Wu P. Astragalus membranaceus stimulates human sperm motility in vitro. Am J Chin Med 1992;20:289-94. 13. Ma J, Peng A, Lin S. Mechanisms of the therapeutic effect of astragalus membranaceus on sodium and water retention in experimental heart failure. Chin Med J (Engl) 1998;111:17-17. 14. Yang YZ, Jin PY, Guo Q, et al. Treatment of experimental Coxsackie B-3 viral myocarditis with Astragalus membranaceus in mice. Chin Med J (Engl) 1990;103:14-8. 15. Xu F, Zhang Y, Xiao S, et al. Absorption and metabolism of Astragali radix decoction: in silico, in vitro, and a case study in vivo. Drug Metab Dispos 2006;28:913-18. 16. Leung AY, Foster S. Encyclopedia of Common Natural Ingredients Used in Food, Drugs and Cosmetics. 2nd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 1996. | |

B |

|---|

Berberisvulg

Scientific name: Berberis vulgaris Family: Berberidaceae. Traditiona Uses: Orally, the fruit of European barberry is used for kidney, urinary tract, and gastrointestinal tract discomforts such as heartburn, stomach cramps, constipation, lack of appetite, liver and spleen disease, for bronchial and lung discomforts, spasms, as a stimulant for circulation, for people susceptible to infection, and as a supplemental source of vitamin C. The bark, root, and root bark of European barberry are also used orally for ailments and complaints of the GI tract, liver, gallbladder, kidney and urinary tract, respiratory tract, heart and circulatory system, to lower a fever, "blood purifier", and for narcotic withdrawal. European barberry root bark is used for liver dysfunction, gallbladder disease, jaundice, splenopathy, diarrhea, indigestion, hemorrhoids, renal and urinary tract diseases, gout, rheumatism, arthritis, mid and low back pain, malaria, and leishmaniasis. Safety: Traditionally used as a fruit syrup and preserve.when the fruit is consumed orally in food amounts

Evidence from Scientific Research Very little clinical research has been done. Dental Plaque: Preliminary clinical research suggests that brushing with a European barberry extract gel containing 1% berberine three times daily for 3 weeks significantly reduces plaque index compared to placebo and has similar effects compared to a commercial antiplaque toothpaste (Colgate) Diabetes. Small studies suggests that taking European barberry for 8 weeks does not affect blood sugar control in patients with type 2 diabetes How might it work: The applicable parts of European barberry are the fruit (berry), root, bark, and root bark. Preliminary research suggests that European barberry fruit has antihistaminic and anticholinergic effects Preliminary research suggests berberine might inhibit bacterial sortase, a protein responsible for anchoring gram-positive bacteria to cell membranes. Preliminary clinical research suggests it might be useful for topical treatment of burns and trachoma, a common cause of blindness in developing countries. Unwanted effects: Orally, the use of European barberry and other berberine-containing herbs during pregnancy, lactation, or in newborn infants can cause jaundice as the infant have not yet the capacity to metabolise berberine. No adverse reactions have been reported for berberis vulgaris and no clinical studies have been done. In traditional use it is well tolerated. Berberine, a primary constituent of European barberry, has been used orally in adults in doses up to 2 grams/day for 8 weeks with no adverse effects reported Interactions with drugs/supplements: Anticoagulants/antiplatelet drugs: No reported cases of blood clotting problems have been reported with this herb. However Berberine, one of the many constituents of European barberry, may inhibit platelet aggregation in animal studies so caution is advised. Blood sugar control: Clinical study demonstrated no blood sugar lowering effect, but advise monitoring for diabetics as theoretically a lowering of blood sugar is possible. Lowering Blood Pressure: Theoreticall an effect of lowering blood pressure may add to the therapeutic effect of medication, as a precaution remain seated or lie down for 30 minutes after the first 2-3 doses and monitor effect. Transplant antirejection Cyclosporin A (CsA): The constituent Berberine can markedly elevate the blood concentration of CsA in renal-transplant recipients in both clinical and pharmacokinetic studies. This combination may allow a reduction of the CsA dosage. The mechanism for this interaction is most likely explained by inhibition of cytochrome CYP3A4 in the liver and/or small intestine. CYP3A4 Metabolised Drugs: Theoretically blood levels can be elevated or lowered. Common drugs include the SSRI antidepressants, Some Statins (lovastatin), some antibiotics, for full list see http://www.pharmacytimes.com/publications/issue/2008/2008-09/2008-09-8687 Effect on lab. tests: Theoretically, European barberry might increase bilirubin levels. This has been demonstrated with isolated berberine constituent, but not specifically with European barberry. Berberine displaces bilirubin from albumin and increases total and unbound bilirubin concentrations. Effect on conditions or disorders: BLEEDING DISORDERS: Berberine, a constituent of European barberry, might inhibit platelet aggregation. Theoretically, European barberry might increase the risk of bleeding and interfere with therapy in patients with bleeding conditions. Dose: ORAL: No typical dosage. Traditionally, a typical dose is one cup tea.To make tea, steep 1-2 teaspoons of whole or squashed berries in 150 mL boiling water 10-15 minutes and strain or steep 2 grams of root bark in 250 mL boiling water 5-10 minutes and strain. Root bark is typically used as a tincture (1:10), 20-40 drops per day. | |

Black CohoshAlso Known As: Cimicifuga, Scientific Name: Cimicifuga racemosa. Family: Ranunculaceae. People Use This For: Black Cohosh is used for symptoms of menopause, inducing labor in pregnant women, premenstrual syndrome (PMS), painful periods, nervous tension, indigestion, rheumatism, and as a mild sedative. Safety: Possibly safe when used orally and appropriately. Black cohosh has been safely used in some studies lasting up to a year; 1,2,3 There is concern that black cohosh might cause liver damage in some patients. Several case reports link black cohosh to liver failure or autoimmune hepatitis; 4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 however, there is no conclusive evidence that black cohosh is the cause of liver damage in these patients.18 Until more is known, monitor liver function in patients who take black cohosh for more than three months. Analysis of 9 Cases of Suspected association between Black Cohosh and Hepatitis concluded that there is little if any hepatotoxic risk by the use of Black Cohosh in these cases. Menopause 2009 Sep-Oct: 16(5):956-65 Teschke R, Bahre R, Fuchs J, Wolff A. It is concluded that the use of BC may not exert an overt toxicity risk, but quality problems in a few BC products were evident that require additional regulatory quality specifications. Ann Hepatology. 2011 Jul-Sep;10(3):249-59 Pregnancy and Lactation: Refer to Medical Herbalist Effectiveness: POSSIBLY EFFECTIVE Menopausal symptoms. Some black cohosh extracts seem to modestly reduce symptoms of menopause, such as hot flashes. However, there is considerable variability in the preparations used in clinical trials, and in the results obtained.19 INSUFFICIENT RELIABLE EVIDENCE to RATE Osteoporosis: Preliminary clinical research suggests that postmenopausal women who take a specific black cohosh extract CR BNO 1055 (Klimadynon/Menofem, Bionorica AG) 40 mg/day have increased levels of bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (bALP), which is a marker of bone formation, after 12 weeks of treatment. 20 However, it is not known if this black cohosh extract can increase bone mineral density or decrease the risk of fracture. More evidence is needed to rate black cohosh for these uses. Mechanism of Action: The applicable parts of black cohosh are the rhizome and root. The active constituents of black cohosh include phytosterin; isoferulic acid; fukinolic acid; caffeic acid; salicylic acid; sugars; tannins; long-chain fatty acids; and triterpene glycosides, including acetein, cimicifugoside, and 27-deoxyactein.21,22 Black cohosh has estrogen-like effects (not estrogenic effects) that are exerted by an unknown mechanism.21,23,20 Adverse Reactions: Black cohosh can commonly cause gastrointestinal upset.4,24,25 Black cohosh has associated with weakness and muscle damage in one case. In another case, a single patient developed symptoms of cutaneous pseudolymphoma 6 months after starting a specific black cohosh extract (Remifemin). Symptoms resolved within 12 weeks of discontinuing black cohosh.26 There are two case reports of cutaneous vasculitis in menopausal women who took black cohosh-containing products. In these cases, both women were taking a combination product containing black cohosh 40 mg (Estroven, Amerifit Brands). Symptoms resolved within 3 months of discontinuing the product.27 Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: Refer to a Medical Herbalist. Interactions with Drugs: Atorvastatin (Lipitor) One report of significant interaction. Chemotherapy: Refer to a Medical Herbalist. Hepatotoxic Drugs: Refer to a Medical Herbalist. Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: Liver Function Tests: Elevated liver function tests have not been documented in clinical trials.20 Theoretically, some patients taking black cohosh might experience elevated liver function tests. Interactions with Diseases or Conditions: Breast Cancer: Refer to Medical Herbalist. Hormone-Sensitive Cancers/Conditions: Black cohosh doesn't seem to affect estrogen receptors. Refer to Medical Herbalist. Kidney Transplant: Refer to Medical Herbalist. Liver Disease: Refer to Medical Herbalist. Dosage/Administration: Dr Clare’s Blend: 1gm/day Oral: 0.5-1gms/day Specific References: BLACK COHOSH 1. Raus K, Brucker C, Gorkow C, Wuttke W. First-time proof of endometrial safety of the special black cohosh extract (Actaea or Cimicifuga racemosa extract) CR BNO 1055. Menopause 2006;13:678-91. Newton KM, Reed SD, LaCroix AZ, et al. Treatment of vasomotor symptoms of menopause 2. with black cohosh, mulitbotanicals, soy, hormone therapy, or placebo. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:869-79. Available at: http://www.annals.org/cgi/reprint/145/12/869.pdf. 3. Geller SE, Shulman LP, van Breemen RB, et al. Safety and efficacy of black cohosh and red clover for the management of vasomotor symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause 2009;16:1156-66. 4. Whiting PW, Clouston A, Kerlin P. Black cohosh and other herbal remedies associated with acute hepatitis. Med J Aust 2002;177:440-3. 5. Lontos S, Jones RM, Angus PW, Gow PJ. Acute liver failure associated with the use of herbal preparations containing black cohosh. Med J Aust 2003;179:390-1. 6. Cohen B, Schardt D. Center for Science in the Public Interest. Letter to Food and Drug Administration. Commissioner Mark McClellan, MD, PhD. March 4, 2004. Cohen SM, O'Connor AM, Hart J, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis associated with the use of 7. black cohosh: a case study. Menopause 2004;11:575-7. 8. Levitsky J, Alli TA, Wisecarver J, Sorrell MF. Fulminant liver failure associated with the use of black cohosh. Dig Dis Sci 2005;50:538-9. 9. MHRA. Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) - risk of liver problems. Herbal Safety News IdcService=SS_GET_PAGE&useSecondary= true&ssDocName=CON2024131&ssTargetNodeId=663. 10. Lynch CR, Folkers ME, Hutson WR. Fulminant hepatic failure associated with the use of black cohosh: a case report. Liver Transpl 2006;12:989-92. 11. Chow ECY, Teo M, Ring JA, Chen JW. Liver failure associated with the use of black cohosh for menopausal symptoms. Med J Aust 2008;188:420-2. 12. Mahady GB, Low Dog T, Barrett ML, et al. United States Pharmacopeia review of the black cohosh case reports of hepatotoxicity. Menopause 2008;15:628-38. 13. Hepatotoxicity with black cohosh. Australian Adv Drug Reactions Bull 2006;25:6. Available at: www.tga.gov.au/adr/aadrb/aadr0604.htm#a1. 14. Dunbar K, Solga SF. Black cohosh, safety, and public awareness. Liver Int 2007;27:1017. 15. Patel NM, Derkits RM. Possible increase in liver enzymes secondary to atorvastatin and black cohosh administration. J Pharm Pract 2007;20:341-6. 16. Joy D, Joy J, Duane P. Black cohosh: a cause of abnormal postmenopausal liver function tests. Climacteric 2008;11:84-8. 17. Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee. Black cohosh and liver toxicity - an update. Aust Adv Drug Reactions Bull 2007;26:11. 18. Teschke R, Bahre R, Genthner A, et al. Suspected black cohosh hepatotoxicity - challenges July 2006. Available at: http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/idcplg? and pitfalls of causality assessment. Maturitas 2009;63:302-14. 19. Shams T, Setia MS, Hemmings R, et al. Efficacy of black cohosh-containing preparations on menopausal symptoms: a meta-analysis. Altern Ther Health Med 2010;16:36-44. 20. Wuttke W, Gorkow C, Seidlova-Wuttke D. Effects of black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) on bone turnover, vaginal mucosa, and various blood parameters in postmenopausal women: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, and conjugated estrogens-controlled study. Menopause 2006;13:185-96. 21. Kruse SO, Lohning A, Pauli GF, et al. Fukiic and piscidic acid esters from the rhizome of Cimicifuga racemosa and the in vitro estrogenic activity of fukinolic acid. Planta Med 1999;65:763-4. 22. Loser B, Kruse SO, Melzig MF, Nahrstedt A. Inhibition of neutrophil elastase activity by cinnamic acid derivatives from Cimicifuga racemosa. Planta Med 2000;66:751-3. Einer-Jensen N, Zhao J, Andersen KP, Kristoffersen K. Cimicifuga and Melbrosia lack 23. oestrogenic effects in mice and rats. Maturitas 1996;25:149-53. 24. Pepping J. Black cohosh: Cimicifuga racemosa. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1999;56:1400-2. 25. Liske E. Therapeutic efficacy and safety of Cimicifuga racemosa for gynecologic disorders. Adv Ther 1998;15:45-53. 26. Meyer S, Vogt T, Obermann EC, et al. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma induced by Cimicifuga racemosa. Dermatology 2007;214:94-6. 27. Ingraffea A, Donohue K, Wilkel C, Falanga V. Cutaneous vasculitis in two patients taking an herbal supplement containing black cohosh. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;56:S124-6. | |

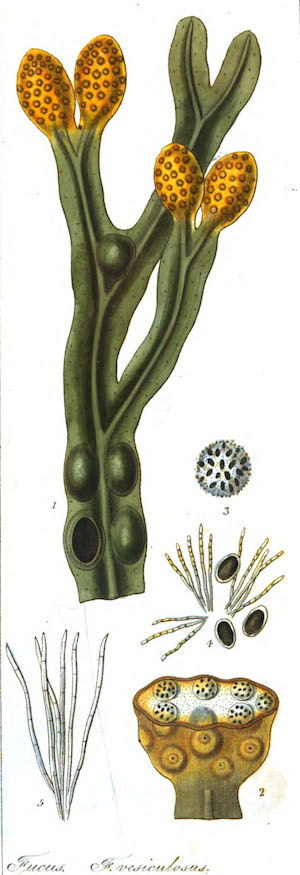

Bladderwrack

Scientific Name: Fucus vesiculosus; Ascophyllum nodosum; other Fucus species. Family: Fucaceae. People Use This For: Bladderwrack is used for thyroid disorders, iodine deficiency, goiter, obesity, arthritis, and rheumatism, "blood cleansing", to increase energy, constipation, bronchitis, decreased resistance to disease, and anxiety. Topically, bladderwrack is used for skin diseases, burns, aging skin, and insect bites. Safety: No concerns regarding safety when used orally in appropriate doses. It is important to obtain traceable supply free from contamination (1 case of contamination with heavy metals reported in the 1970’s).1,2 Pregnancy and Lactation: Refer to a Medical Herbalist Effectiveness: INSUFFICIENT RELIABLE EVIDENCE to RATE Obesity: Preliminary clinical research suggests that bladderwrack in combination with lecithin and vitamins doesn't result in sustained weight loss. More evidence is needed to rate bladderwrack for this use (combined lecithin, kelp, multivitamin preparation involving 120 women over 2 years). 3 Mechanism of Action: The applicable part of bladderwrack is the entire plant. Bladderwrack is a brown seaweed. Bladderwrack contains high concentrations of iodine, which is present in varying amounts. Bladderwrack is a source of fiber, minerals such as iron, and vitamin B12.2 Preliminary clinical research suggests bladderwrack may normalize the menstrual cycle and have estrogen balancing effects in premenopausal women. It may also balance progesterone effects4 (case reports on three patients). Preliminary clinical research suggests topical administration of bladderwrack extract might reduce skin thickness and other signs of aging.5 Adverse Reactions: Excess Iodine intake is rare in humans outside of radiation contamination or excessive amounts of seaweed (or seaweed extracts) intake over a prolonged period. There is one case report of heavy metal poisoning where arsenic poisoning occurred with ingestions of a contaminated kelp product. 6 Another case of arsenic-related poisoning with bladderwrack ingestion 400 mg three times a day for 3 months resulted in kidney damage.7 Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: Avoid Iodine supplements at the same time. Interactions with Drugs: Antithyroid Drugs: Theoretically, may result in additive hypothyroid activity, and may lower the level of availableThyroid hormones.8 Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: Radioactive Iodine Uptake: Theoretically, bladderwrack might interfere with the results of thyroid function tests using radioactive iodine uptake.2 Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH): Theoretically, bladderwrack might increase serum TSH levels and test results.8 Thyroxine (T4): Theoretically, bladderwrack might increase serum T4 levels and test results.8 Interactions with Diseases or Conditions: Iodine Allergy: Avoid bladderwrack use in people sensitive to iodine.8 Thyroid Disorders: Prolonged use or excessive amounts of iodides may exacerbate thyroid gland problems.8 Dosage/Administration: Dr Clare’s Blends: 1 gm per day No typical dosage. Specific References: BLADDERWRACK 1. Baker DH. Iodine toxicity and its amelioration. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2004;229:473-8. 2. Phaneuf D, Cote I, Dumas P, et al. Evaluation of the contamination of marine algae (Seaweed) from the St. Lawrence River and likely to be consumed by humans. Environ Res 1999;80:S175-S182. 3. Bjorvell H, Rössner S. Long-term effects of commonly available weight reducing programmes in Sweden. Int J Obes 1987;11:67-71. 4. Skibola CF. The effect of Fucus vesiculosus, an edible brown seaweed, upon menstrual cycle length and hormonal status in three pre-menopausal women: a case report. BMC Complement Altern Med 2004;4:10. 5. Fujimura T, Tsukahara K, Moriwaki S, et al. Treatment of human skin with an extract of Fucus vesiculosus changes its thickness and mechanical properties. J Cosmet Sci 2002;53:1- Pye KG, Kelsey SM, House IM, et al. Severe dyserythropoeisis and autoimmune 6. thrombocytopenia associated with ingestion of kelp supplement. Lancet 1992;339:1540. 7. Conz PA, La Greca G, Benedetti P, et al. Fucus vesiculosus: a nephrotoxic alga? Nephrol Dial Transplant 1998;13:526-7. 8. Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2002. Available at: www.nap.edu/books/0309072794/html/. | |

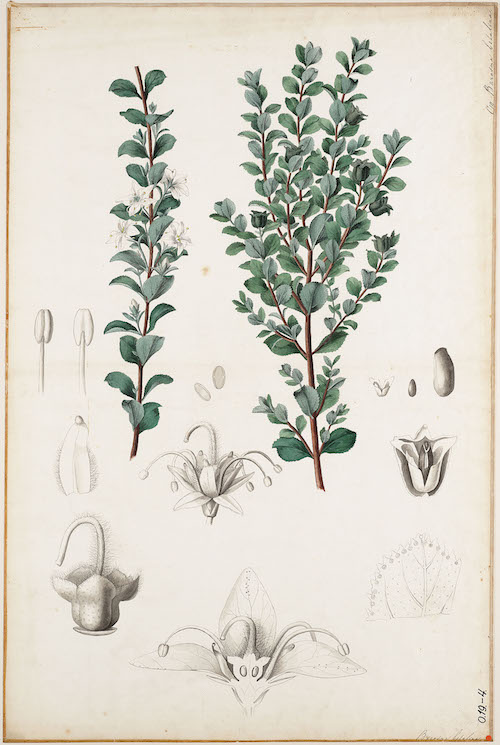

Bogbean

Buckbean, Marsh Trefoil, Menyanthes, Water Shamrock. Scientific Name: Menyanthes trifoliata. Family: Menyanthaceae. People Use This For: Bogbean is used for rheumatism, rheumatoid arthritis, loss of appetite, and dyspepsia. In food manufacturing, bogbean is used as a flavoring agent. Safety: No concerns regarding safety when used orally in amounts commonly found in foods.1 No concerns regarding safety when used orally in medicinal amounts,2 no clinical reports of problems. Pregnancy and Lactation: Refer to a Medical Herbalist. Effectiveness: There is insufficient scientific information available to comment. Mechanism of Action: The applicable part of bogbean is the leaf. The bitter principles, or iridoids, can stimulate saliva and gastric juices (3,1). Bogbean can have purgative actions (1). Adverse Reactions: None reported for normal dosage. Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: None reported Interactions with Drugs: None reported. Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: None known. Interactions with Diseases or Conditions: None reported. Dosage/Administration: Dr Clare’s Blends:1gm per day Oral: The typical dose of bogbean is 1-3 grams of the dried leaf three times daily or as a tea three times daily. Specific References: BOGBEAN Newall CA, Anderson LA, Philpson JD. Herbal Medicine: A Guide for Healthcare 1. Professionals. London, UK: The Pharmaceutical Press, 1996. 2. McGuffin M, Hobbs C, Upton R, Goldberg A, eds. American Herbal Products Association's Botanical Safety Handbook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, LLC 1997. 3. Blumenthal M, ed. The Complete German Commission E Monographs: Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines. Trans. S. Klein. Boston, MA: American Botanical Council, 1998. | |

Boneset

Agueweed, Crosswort, Eupatoire, Eupatorio, Feverwort, Indian Sage, Sweating Scientific Name: Eupatorium perfoliatum. Family: Asteraceae/Compositae. People Use This For: Orally, boneset is used as an antipyretic, diuretic, laxative, emesis, and cathartic. Safety: POSSIBLY UNSAFE: When used orally in excessive amounts. Large doses are both cathartic and emetic. Though the alkaloids have not been characterized, hepatotoxic pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs) are common in this genus (3). PREGNANCY AND LACTATION: POSSIBLY UNSAFE ...when used orally, due to possible hepatotoxic pyrrolizidine alkaloid content (3); avoid using. Effectiveness: There is insufficient reliable information available about the effectiveness of boneset. Mechanism of Action: The applicable parts of boneset are the dried leaf and flowering parts. Preliminary research suggests boneset might have cytotoxic and mild antibacterial activity (4). Adverse Reactions: Report an Adverse Reaction to BONESET Orally, boneset can cause an allergic reaction in individuals sensitive to the Asteraceae / Compositae family. Members of this family include ragweed, chrysanthemums, marigolds, daisies, and many other herbs. Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: HEPATOTOXIC : Concomitant use is contraindicated due to the risk of additive toxicity. Herbs containing hepatotoxic PAs include borage, butterbur, coltsfoot, comfrey, gravel root, hemp agrimony, hound's tongue, and the Senecio species plants dusty miller, alpine ragwort, groundsel, golden ragwort, and tansy ragwort (2). PYRROLIZIDINE ALKALOID (PA)-CONTAINING Interactions with Drugs: None known. Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: None known. Interactions with Diseases or Conditions: CROSS-ALLERGENICITY: Boneset can cause an allergic reaction in individuals sensitive to the Asteraceae/Compositae family. Members of this family include ragweed, chrysanthemums, marigolds, daisies, and many other herbs. Dosage/Administration: ORAL: Traditionally one cup of tea, prepared by steeping 1-2 grams herb in 150 mL boiling water, has been used three times daily. The liquid extract, 1:1 in 25% alcohol, has been used 1-2 mL three times daily. 1-4 mL of the tincture, 1:5 in 45% alcohol, has also been used three times daily (1). Specific References: THYME 1. Newall CA, Anderson LA, Philpson JD. Herbal Medicine: A Guide for Healthcare 2. Chojkier M. Hepatic sinusoidal-obstruction syndrome: toxicity of pyrrolizidine 3. Roeder E. Medicinal plants in Europe containing pyrrolizidine alkaloids. Pharmazie 4. Habtemariam S, Macpherson AM. Cytotoxicity and antibacterial activity of ethanol extract from leaves of a herbal drug, boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum). Phytother Res 2000;14:575-7. | |

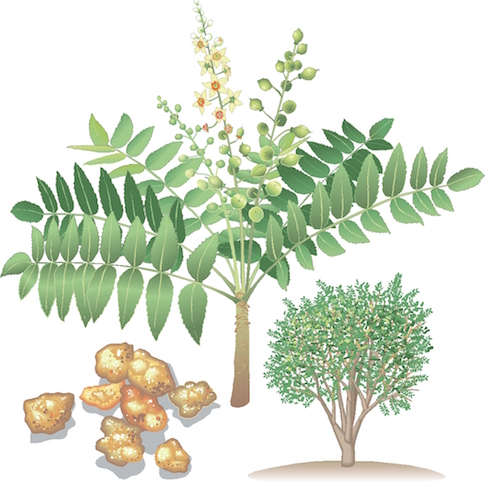

Boswellia

Also known as: Indian Frankincense, Indian Olibanum, Ru Xiang, Salai Guggul. Scientific name: Boswellia serrata. Botanical Family: Burseraceae. Part used: The medicinal part of Indian frankincense plant is the gum resin. The gum resin is obtained by pulling away the bark of the Indian frankincense tree. Traditional use. Indian frankincense is used for osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatism, bursitis, and tendonitis. Other uses include ulcerative colitis, abdominal pain, asthma, allergic rhinitis, sore throat, painful menstruation, acne, and cancer. It is also used as a stimulant, respiratory antiseptic, diuretic, and for stimulating menstrual flow. Safety. There are no safety concerns when used orally and appropriately. Indian frankincense has been safely used in several clinical trials lasting up to ninety days. (1,2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10) Pregnancy: Safe when used orally in amounts commonly found in foods.(11) For medicinal use consult an Herbal Medicine Physician. Breastfeeding: Safe when used orally in amounts commonly found in foods.(11) For medicinal use consult an Herbal Medicine Physician. Constituents Boswellic acids (triterpenoids) Essential oils including cymene and thujone Scientific evidence. Osteoarthritis. Some clinical research shows that taking specific Indian frankincense extracts can reduce symptoms of osteoarthritis. In two clinical trials, using a specific Indian frankincense extract (5-Loxin) 100 mg daily or 250 mg daily significantly improved pain and functionality scores in patients with osteoarthritis after 90 days of treatment. Pain scores were reduced by about 32% to 65%. Patients began to have significant improvement within 7 days of treatment. The extract used in this study was standardized and enriched to contain 30% of the boswellic acid AKBA. (8,9) One clinical trial evaluated another specific Indian frankincense extract (Aflapin) 100 mg daily. This extract significantly improved pain and functionality scores in patients with osteoarthritis after 90 days of treatment. Pain scores were reduced by about 47%. Patients began to have significant improvement within 7 days of treatment. The extract used in this study was standardized and enriched to contain 20% of the boswellic acid AKBA. (9) In a preliminary crossover trial, taking a different Indian frankincense extract, 333mg daily also significantly reduced symptoms of osteoarthritis, such as knee pain and swelling. (3) Ulcerative colitis. Two clinical trials show that taking Indian frankincense can improve some symptoms of ulcerative colitis and some pathological measures. In one study, taking whole plant Indian frankincense resin 350 mg three times daily significantly improved symptoms and disease markers in patients with ulcerative colitis. In this study, about 82% of patients taking Indian frankincense went into remission compared to 75% taking the commonly prescribed drug sulfasalazine.(2) In another preliminary clinical study, taking whole plant Indian frankincense resin 300 mg three times for 6 weeks improved symptoms and some measures of disease pathology in about 90% of patients. In this study 70% of patients taking Indian frankincense went into remission compared to 40% taking sulfasalazine 3 grams daily. (7) Asthma. There is some preliminary evidence that taking Indian frankincense extract orally might help asthma. It may improve forced expiratory volume, reduce the number of asthma attacks, and decrease clinical signs of asthma. (1) Crohn's disease. There is preliminary evidence that taking Indian frankincense extract orally might reduce some symptoms of Crohn’s disease. One clinical study found that it worked as well as mesalamine (Asacol, Pentasa) for Crohn's disease;(6) however, other clinical research shows that taking Indian frankincense 800 mg orally three times a day did not increase rates of remissions and quality of life any more than placebo in patients with Crohn's disease. (12) Rheumatoid arthritis. There is conflicting research about the usefulness of Indian frankincense extract taken orally for rheumatoid arthritis. (4,5) Mechanism of action. The principle constituents of Indian frankincense are boswellic acid and alpha- and beta-boswellic acid, which are thought to have anti-inflammatory properties. (13,14) The boswellic acid (AKBA) constituent appears to be the most potent anti-inflammatory constituent. (14) The gum resin also contains up to 16% essential oils including alpha-thujene and p-cymene. (15) In preliminary research, some Indian frankincense extracts show anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and anti-arthritis effects; however, not all Indian frankincense-containing products seem to have these effects. (3) Boswellic acids, especially AKBA, inhibit 5-LOX enzymes and reduce leukotriene synthesis and inhibit leukocyte elastase, which are the likely mechanisms for its anti-inflammatory properties. Boswellic acids may also have a disease modifying effect by decreasing the breakdown of glycosaminoglycan and thus reducing cartilage damage. Indian frankincense may also inhibit mediators of autoimmune disorders. It seems to reduce production of antibodies and cell-mediated immunity. (3,7,16,17) Indian frankincense may be useful in treating cancer. Preliminary research suggests that boswellic acids have an anti-proliferative effect and an effect of increasing the rate of cell death (apoptosis) in cancer cells. (16) Preliminary research suggests that boswellic acids stabilize mast cells, this suggests usefulness for asthma and other allergic conditions.(18) Other preliminary research suggests that boswellic acids might help prevent organ rejection and ischemia/reperfusion injury.(19) Indian frankincense has an elimination half-life of 6 hours from the blood stream.(20) Adverse reactions. Indian frankincense is well-tolerated. Side effects reported in clinical trials did not occur more commonly than placebo. (8) Some reported side effects include diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, and heartburn. (3,7,8 ,9 ,10) No serious adverse events have been documented.(10) Interactions with herbs and supplements. None known. Interactions with drugs. None known. Interactions with foods. None known. Interactions with lab tests. None known. Interactions with diseases or conditions. None known. Dosage. For osteoarthritis, a specific Indian frankincense extract (5-Loxin) 100 mg daily or 250 mg daily has been used.(8) Indian frankincense extract 333 mg three times daily has been used. (3) For rheumatoid arthritis, Indian frankincense extract 3,600 mg daily has been used. (4) For Crohn's disease, 800 mg three times daily has been used. (21) For ulcerative colitis, a gum resin preparation of 300-350 mg three times daily has been used. (2,7) For asthma, 300 mg three times daily has been used. (1) | |

Buchu

Barosmae Folium. Scientific Name: Barosma betulina People Use This For: Orally, buchu is used as a urinary tract disinfectant in cystitis, urethritis, prostatitis, benign prostatic hyperplasia and kidney infections. In manufacturing, the oil from buchu is used to give a fruit flavor (often black currant) to foods. Safety: No concerns regarding safety, available studies validate this statement, when the leaf is used in amounts commonly found in foods. Buchu has Generally Recognized As Safe status (GRAS) for use in foods in the US.1 No converns regarding safety when the leaf is used orally and appropriately in medicinal amounts.2,3 Pregnancy and Lactation: Refer to a Medical Herbalist. Effectiveness: Not enough scientific information gathered to offer a comment Mechanism of Action: The applicable part of buchu is the leaf. Buchu camphor (also known as diosphenol) is the principal constituent of the oil. Researchers believe this constituent may be responsible for buchu's reported diuretic and antiseptic effects.4 Adverse Reactions: Occasional digestive upset if taken on an empty stomach.R1 pp.311 Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: None Interactions with Drugs: Lithium: Because of diuretic effect.R3 pp.163-164 Diuretics: Effect can be additive.R4 pp.192,204,215 Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: None known. Interactions with Diseases or Conditions: Surgery: Tell patients to discontinue buchu at least 2 weeks before elective surgical procedures. Dosage/Administration: Oral: The typical dose is 1 cup of tea (steep 1 gram dry leaf in 150 mL boiling water 5-10 minutes, strain) several times per day.5 Specific References: BUCHU 1. FDA. Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Office of Premarket Approval, EAFUS: A food additive database. Available at: vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/eafus.html. 2. Blumenthal M, ed. The Complete German Commission E Monographs: Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines. Trans. S. Klein. Boston, MA: American Botanical Council, 1998. 3. McGuffin M, Hobbs C, Upton R, Goldberg A, eds. American Herbal Products Association's Botanical Safety Handbook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, LLC 1997. 4. Foster S, Tyler VE. Tyler's Honest Herbal: A Sensible Guide to the Use of Herbs and Related Remedies. 3rd ed., Binghamton, NY: Haworth Herbal Press, 1993. 5. Wichtl MW. Herbal Drugs and Phytopharmaceuticals. Ed. N.M. Bisset. Stuttgart: Medpharm GmbH Scientific Publishers, 1994. | |

Burdock Root

Arctium, Beggar's Buttons, Burr Seed, Clotbur, Cocklebur. Scientific Name: Arctium lappa; Arctium minus; Arctium tomentosum. Family: Asteraceae/Compositae. People Use This For: Burdock is used as a diuretic, "blood purifier", antimicrobial, and an antipyretic. It is also used to treat gastrointestinal complaints, rheumatism, gout, cystitis, and chronic skin conditions including acne and psoriasis. It is also used for hypertension, arteriosclerosis, hepatitis, and other inflammatory conditions. SourceURL:file://localhost/Users/ruthruane/Downloads/Herbal%20Medicine-Newest.doc Burdock is also used for treating colds, catarrh. Topically, burdock is used for dry skin, acne, psoriasis, and eczema. The root of burdock is consumed as a food. Safety: No concerns regarding safety when used in amounts commonly found in foods.9,10 Pregnancy and Lactation: Refer to a Medical Herbalist. Effectiveness: There is insufficient scientific information available to comment on the effectiveness of burdock. Mechanism of Action: The applicable relevant part of burdock is the root. Extracts of burdock root appear to have cough suppressant activity and may increase immunological activity.11 Other preliminary research suggests it might have anti-inflammatory and free radical scavenging activity.12 Burdock root extract might also protect the liver from toxicity caused by ethanol and carbon tetrachloride, possibly due to its antioxidant activity.9 Adverse Reactions: An isolated report of an allergic reaction causing anaphylaxis.10 Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: SourceURL:file://localhost/Users/ruthruane/Downloads/Herbal%20Medicine-Newest.doc None known. Dosage/Administration: No typical dosage Specific References: BURDOCK 9. Lin SC, Lin CH, Lin CC, et al. Hepatoprotective effects of Arctium lappa Linne on liver injuries induced by chronic ethanol consumption and potentiated by carbon tetrachloride. J Biomed Sci 2002;9:401-9. 10. Sasaki Y, Kimura Y, Tsunoda T, Tagami H. Anaphylaxis due to burdock. Int J Dermatol 2003;42:472-3. 11. Kardosova A, Ebringerova A, Alfoldi J, et al. A biologically active fructan from the roots of Arctium lappa L., var. Herkules. Int J Biol Macromol 2003;33:135-40. 12. Lin CC, Lu JM, Yang JJ, et al. Anti-inflammatory and radical scavenge effects of Arctium lappa. Am J Chin Med 1996;24:127-37. | |

C |

|---|

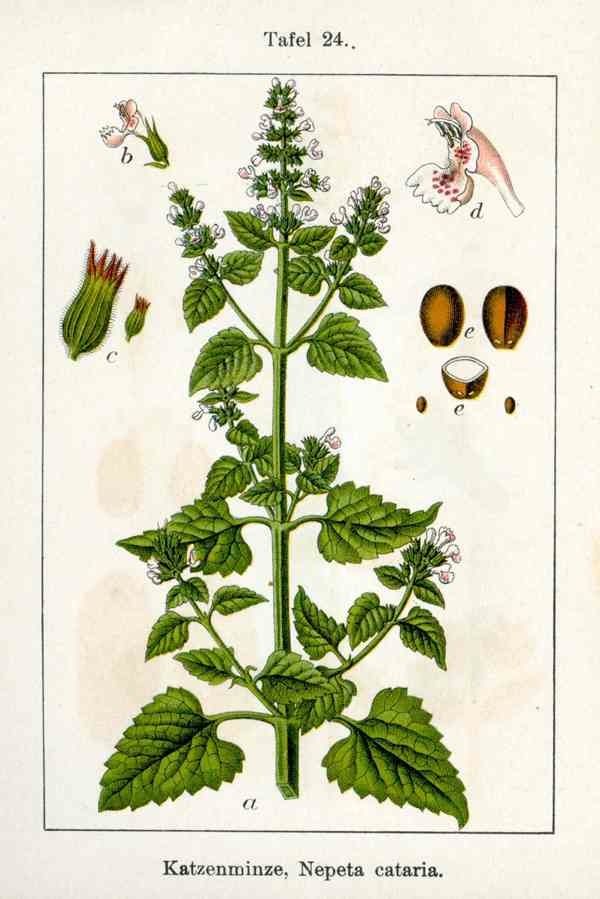

Catmint

Cataire, Catmint, Catswort, Chataire, Field Balm, Hierba Gatera, Menta de Gato, Menthe des Chats. CAUTION: See separate listing for Schizonepeta. Scientific Name: Nepeta cataria. Family: Lamiaceae/Labiatae. People Use This For: Catnip is used for insomnia; migraine headaches; cold; flu; swine flu; fever; hives; and gastrointestinal (GI) upset, including indigestion, colic, cramping, and flatulence. It is also used orally for conditions associated with anxiety, diuresis, as a tonic, for upper respiratory tract infections, and headaches. Additionally, catnip is also used orally for lung and uterine congestion, eradicating worms, and for initiating menses in girls with delayed onset of menstruation. Topically, catnip has been used for arthritis, hemorrhoids, and as a poultice to relieve swelling. As an inhalant, catnip is smoked for respiratory conditions and recreationally for inducing a euphoric high. In manufacturing, catnip is used as a pesticide and insecticide. Safety: POSSIBLY SAFE ...when used orally and appropriately (2,3). Significant adverse effects have not been reported when catnip tea is used in cupful amounts (62). POSSIBLY UNSAFE : when used orally in excessive doses. Higher doses may be associated with significant adverse effects (62). ...when inhaled by smoking dried leaves. Smoking the dried leaves of catnip has been associated with a euphoric high (2), which might impair judgment; however, whether catnip can truly produce this effect in humans remains controversial (2). There is insufficient reliable information available about the safety of topically applied catnip. CHILDREN: POSSIBLY UNSAFE ...when used orally. One child developed stomach pain and irritability followed by lethargy and hypnotic state after ingesting catnip leaves and tea (1,5). PREGNANCY: LIKELY UNSAFE ...when used orally. Catnip tea has been reported to have uterine stimulant properties (3); avoid using. LACTATION: Insufficient reliable information available; avoid using. Effectiveness: There is insufficient reliable information available about the effectiveness of catnip. Mechanism of Action: The applicable part of catnip is the flowering tops. The pharmacological effect that catnip is famous for is the euphoric state it induces in cats. It is thought that the constituent cis-trans-nepetalcatone produces the characteristic stimulation in cats only when they smell it (1). Although humans have used catnip to induce a euphoric high, whether or not this effect actually occurs in humans is controversial. In humans, the constituent nepetalactone is thought to be responsible for catnip's calming effects in insomnia, anxiety, gastrointestinal (GI) conditions, and migraine headache. Nepetalactone is the major component (80- 95%) of the volatile oil of catnip and is structurally related to the valepotriates found in valerian. Catnip provides approximately 0.2-1% volatile oil. Catnip reportedly also has antipyretic and diaphoretic effects, which have been attributed to its use for colds, flu, and fever. Other reported pharmacological effects, include diuretic and stimulation of gallbladder activity (2). Adverse Reactions: Report an Adverse Reaction to CATNIP Catnip abuse may result in headache and malaise. Large amounts of tea may cause vomiting (2). One case report exists of a nineteen-month-old child who developed a stomachache and irritability, followed by lethargy and a hypnotic state after ingesting raisins soaked in catnip tea and chewing on the tea bag (5). Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: HERBS AND SUPPLEMENTS WITH SEDATIVE PROPERTIES: Theoretically, concomitant use of catnip with herbs that have sedative properties might enhance therapeutic and adverse effects. Some of these supplements include 5-HTP, calamus, California poppy, catnip, hops, Jamaican dogwood, kava, St. John's wort, skullcap, valerian, yerba mansa, and others. Interactions with Drugs: CNS DEPRESSANTS <<interacts with>> CATNIP Interaction Rating = Moderate Be cautious with this combination. Severity = High • Occurrence = Possible • Level of Evidence = D Theoretically, concomitant use with drugs with sedative properties may cause additive effects and side effects (4). LITHIUM <<interacts with>> CATNIP Interaction Rating = Moderate Be cautious with this combination. Catnip is thought to have diuretic properties. Theoretically, due to these potential Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: None known. Interactions with Diseases or Conditions: PELVIC INFLAMMATORY DISEASE (PID) and MENORRHAGIA: Because catnip is also used to stimulate menstruation, theoretically it is contraindicated in pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and excessive menstrual bleeding (3). SURGERY: Catnip has CNS depressant effects. Theoretically, catnip might cause additive CNS depression when combined with anesthesia and other medications during and after surgical procedures. Tell patients to discontinue catnip at least 2 weeks before elective surgical procedures. Dosage/Administration: ORAL: People typically use two 380 mg capsules three times daily at meals or prepared as a tea using 1-2 teaspoons in 6 ounces of boiling water. Specific References: Catmint 1. Foster S, Tyler VE. Tyler's Honest Herbal: A Sensible Guide to the Use of Herbs and Related Remedies. 3rd ed., Binghamton, NY: Haworth Herbal Press, 1993. 2. The Review of Natural Products by Facts and Comparisons. St. Louis, MO: Wolters Kluwer Co., 1999. 3. McGuffin M, Hobbs C, Upton R, Goldberg A, eds. American Herbal Products Association's Botanical Safety Handbook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, LLC 1997. 4. Brinker F. Herb Contraindications and Drug Interactions. 2nd ed. Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications, 1998. 5. Osterhoudt KC, Lee SK, Callahan JM, Henretig FM. Catnip and the alteration of human consciousness. Vet Hum Toxicol 1997;39:373-5. | |

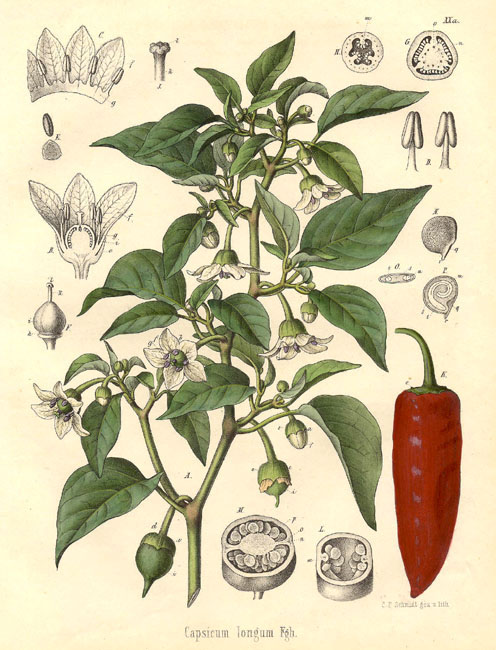

Cayenne

African Bird Pepper, African Chillies, African Pepper, Aji, Bird Pepper, Capsaicin, Capsaïcine, Cayenne, Cayenne Pepper, Chili, Chili Pepper, Chilli, Chillies, Cis-capsaicin, Civamide, Garden Pepper, Goat's Pod, Grains of Paradise, Green Chili Pepper, Green Pepper, Hot Pepper, Hungarian Pepper, Ici Fructus, Katuvira, Lal Mirchi, Louisiana Long Pepper, Louisiana Sport Pepper, Mexican Chilies, Mirchi, Oleoresin Capsicum, Paprika, Paprika de Hongrie, Pili-pili, Piment de Cayenne, Piment Enragé, Piment Fort, Piment-oiseau, Pimento, Poivre de Cayenne, Poivre de Zanzibar, Poivre Rouge, Red Pepper, Sweet Pepper, Tabasco Pepper, Trans-capsaicin, Zanzibar Pepper, Zucapsaicin, Zucapsaïcine. CAUTION: See separate listings for Grains of Paradise and Indian Long Pepper.Scientific Name:Capsicum frutescens; Capsicum annuum; Capsicum chinense; Capsicum baccatum; Capsicum pubescens; Capsicum minimum; and other Capsicum species. People Use This For: Orally, capsicum is used for dyspepsia, flatulence, colic, diarrhea, cramps, toothache, poor circulation, excessive blood clotting, seasickness, swallowing dysfunction, alcoholism, malaria, fever, hyperlipidemia, and preventing heart disease. Intranasally, capsicum is used for allergic rhinitis, perennial rhinitis, migraine headache, cluster headache, sinonasal polyposis, and sinusitis Safety: LIKELY SAFE ...when used orally in amounts typically found in food. Capsicum has Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) status in the US (5). ...when used topically and appropriately. The active capsicum constituent capsaicin used in topical preparations is an FDA-approved over-the-counter product (1). Effectiveness: Pain. Several clinical studies show that applying 0.25% to 0.75% capsaicin cream topically temporarily relieves chronic pain from rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, psoriasis, and neuralgias including shingles and diabetic neuropathy (13, 47). The active capsicum constituent capsaicin, used in topical preparations, is FDA-approved for these uses (1). Back pain. Some evidence shows that applying a capsicum-containing plaster to back can significantly reduce low-back pain compared to placebo (44, 45. 46). Prurigo nodularis. Applying a cream containing 0.025% to 0.3% of the active capsicum constituent capsaicin 4-6 times daily seems to relieve burning sensations, erythema, pruritus, and healing of skin lesions over a period of 2 weeks to 33 months. Symptoms, however, may return after discontinuation of therapy (48). HIV-associated peripheral neuropathy. Applying capsaicin topically does not seem to relieve symptoms of HIV-associated peripheral neuropathy (4). INSUFFICIENT RELIABLE EVIDENCE to RATE Allergic rhinitis. Preliminary research suggests that intranasal treatment with cotton wads soaked in capsaicin applied for 15 minutes and repeated over two days might reduce the severity of experimentally induced allergic rhinitis. Severity of symptoms seems to be decreased for up to two months after capsaicin treatment (30). However, contradictory evidence suggests that patients with allergic rhinitis caused by house dust mites do not have significantly improved symptoms after using a capsaicin solution providing 0.15 mg/dose for up to 7 doses over a 14-day period (42). Swallowing dysfunction. Preliminary evidence suggests that elderly patients at risk for aspiration pneumonia due to swallowing dysfunction have improved swallowing reflexes after dissolving a capsaicin-containing lozenge in their mouth before each meal (27).

Mechanism of Action:

The applicable part of capsicum is the fruit. Capsicum contains the constituent capsaicin, which makes it taste hot. Capsicum powder has been reported to prevent radiation-induced damage to bacterial DNA and thereby protect certain bacteria (Escherichia coli, Bacillus megaterium, and Bacillus pumilus spores) from gamma irradiation, which is used to preserve some foods (6).

Adverse Reactions: Orally, capsicum can cause upper abdominal discomfort including fullness, gas, bloating, nausea, epigastric pain and burning, diarrhea, and belching (12, 22). Sweating and flushing of the head and neck, lacrimation, headache, faintness, and rhinorrhea have also been reported (8, 22). Excessive amounts of capsaicin can lead to gastroenteritis and hepatic necrosis (13). There are also reports of dermatitis in breast-fed infants whose mothers' food is heavily spiced with capsicum (2). Capsicum can also decrease blood coagulation (9). Capsicum oleoresin, an oily extract in pepper self-defense sprays, causes intense eye pain. It can also cause erythema, blepharospasm, tearing, shortness of breath, and blurred vision. In rare cases, corneal abrasions have occurred (20, 21).

Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: ANTICOAGULANT/ANTIPLATELET HERBS AND SUPPLEMENTS: Concomitant use of herbs and supplements that affect platelet aggregation could theoretically increase the risk of bleeding in some people. Some of these herbs include angelica, clove, danshen, garlic, ginger, ginkgo, Panax ginseng, and others. Interactions with Drugs:

ACE INHIBITORS (ACEIs) <<interacts with>> CAPSICUM Interaction Rating = Minor Be watchful with this combination. Severity = Mild • Occurrence = Unlikely • Level of Evidence = D

There is one case report of a topically applied cream containing capsaicin contributing to the cough reflex in a patient using an ACE-inhibitor (26). (12414). But it is unclear if this interaction is clinically significant.

ANTICOAGULANT/ANTIPLATELET DRUGS <<interacts with>> CAPSICUM Interaction Rating = Moderate Be cautious with this combination. Severity = High • Occurrence = Possible • Level of Evidence = D

Theoretically, capsicum might increase the effects and adverse effects of antiplatelet drugs (15, 16). COCAINE <<interacts with>> CAPSICUM Interaction Rating = Moderate Be cautious with this combination. Severity = High • Occurrence = Possible • Level of Evidence = D Theoretically, concomitant use of capsicum (including exposure to the capsicum in pepper spray) and cocaine might increase cocaine effects and the risk of adverse effects, including death (3). THEOPHYLLINE <<interacts with>> CAPSICUMInteraction Rating = Moderate Be cautious with this combination. Severity = Moderate • Occurrence = Possible • Level of Evidence = D

Theoretically, oral administration of capsicum before or at the same time as theophylline might enhance theophylline absorption (14). Interactions with Foods:None known.Interactions with Lab Tests:BLEEDING TIME: Capsicum has led to increased fibrinolytic activity and may lead to prolonged times in coagulation studies (9).Interactions with Diseases or Conditions:DAMAGED SKIN: Capsicum is contraindicated in situations involving injured skin. Do not apply capsicum if the skin is open. | |

Chamomile

Blue Chamomile, Camomilla, Camomille, Camomille Allemande, Chamomilla, Echte Kamille, Feldkamille, Fleur de Camomile, Hungarian Chamomile, Kamillen, Kleine Kamille, Manzanilla, Manzanilla Alemana, Matricaire, Matricariae Flos, Pin Heads, Sweet False Chamomile, True Chamomile, Wild Chamomile. Scientific Name: Matricaria recutita, synonyms Chamomilla recutita, Matricaria chamomilla. Family: Asteraceae/Compositae. People Use This For: Orally, German chamomile is used for flatulence, travel sickness, nasal mucous membrane inflammation, allergic rhinitis, nervous diarrhea, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), fibromyalgia, restlessness, and insomnia. It is also used for gastrointestinal (GI) spasms, colic, inflammatory diseases of the GI tract, GI ulcers associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and alcohol consumption, and as an antispasmodic for menstrual cramps. Topically, German chamomile is used for hemorrhoids; mastitis; leg ulcers; skin, anogenital, and mucous membrane inflammation; and bacterial skin diseases, including those of the mouth and gums. It is also used topically for treating or preventing chemotherapy- or radiation-induced oral mucositis. As an inhalant, German chamomile is used to treat inflammation and irritation of the respiratory tract. In foods and beverages, German chamomile is used as flavor components. In manufacturing, German chamomile is used in cosmetics, soaps, and mouthwashes. Safety: No concerns regarding safety, available studies validate this statement, when used orally in amounts commonly found in foods. German chamomile has Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status in the US.1 No concerns regarding safetywhen used orally, short-term. There is some evidence that German chamomile can be used safely for up to 8 weeks.2,3,4 The long-term safety of German chamomile in medicinal doses is unknown, when used topically; avoid applying it near the eyes.5 Children: No concerns regarding safety when used orally and appropriately, short-term. Preliminary clinical research also suggests that a specific multi-ingredient product containing fennel 164 mg, lemon balm 97 mg, and German SourceURL:file://localhost/Users/ruthruane/Downloads/Herbal%20Medicine-Newest.doc chamomile 178 mg (ColiMil, Milte Italia SPA) is safe in infants when used for up to a week.6 Pregnancy and Lactation: Insufficient reliable information available; avoid using.

Effectiveness: POSSIBLY EFFECTIVE Colic. A clinical trial shows that breast-fed infants with colic who are given a specific multi-ingredient product containing fennel 164 mg, lemon balm 97 mg, and German chamomile 178 mg (ColiMil, Milte Italia SPA) twice daily for a week have reduced crying times compared to placebo.6

Dyspepsia. A specific combination product containing German chamomile (Iberogast, Medical Futures, Inc) seems to improve symptoms of dyspepsia. The combination includes German chamomile plus peppermint leaf, clown's mustard plant, caraway, licorice, milk thistle, celandine, angelica, and lemon balm.7,3 A meta-analysis of studies using this combination product suggests that taking 1 mL orally three times daily over a period of 4 weeks significantly reduces severity of acid reflux, epigastric pain, cramping, nausea, and vomiting compared to placebo.8

Oral mucositis. Using a German chamomile oral rinse (Kamillosan Liquidum) might help prevent or treat mucositis induced by radiation therapy and some types of chemotherapy.2 German chamomile oral rinse seems to prevent or treat mucositis secondary to radiation therapy and some types of chemotherapy including asparaginase (Elspar), cisplatin (CDDP, Platinol-AQ), cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan, Neosar), daunorubicin (DaunoXome), doxorubicin (Adriamycin, Rubex), etoposide (VP-16, Etopophos, VePesid, Toposar), hydroxyurea (Hydrea), mercaptopurine (6-MP, Purinethol), methotrexate (MTX, Rheumatrex), procarbazine (MIH, Mutlane), and vincristine (VCR, Oncovin, Vincasar) (2). However, the rinse doesn't seem to be better than placebo for preventing fluorouracil (5-FU)-induced oral mucositis.9

POSSIBLY INEFFECTIVE Dermatitis. Applying German chamomile cream topically does not seem to prevent dermatitis induced by cancer radiation therapy.10

Mechanism of Action: The applicable part of German chamomile is the flowerhead. Active constituents of German chamomile include quercetin, apigenin, and coumarins, and the essential oils.5

German chamomile might have anti-inflammatory effects. Preliminary research suggests it can inhibit the pro inflammatory enzymes. Other constituents may inhibit histamine related to allergies,5,4 The constituent(s) responsible for the sedative activity of German chamomile are unclear. Preliminary research suggests that extracts of German chamomile might inhibit morphine dependence and withdrawal.11 Other preliminary research suggests that German chamomile flower extract taken orally might have an antipruritic effect.12 Preliminary research suggests that German chamomile blocks slow wave activity in the small intestine, which could slow peristaltic movement.13

Adverse Reactions: Orally, German chamomile tea can cause allergic reactions including severe reactions in some patients.14

Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: HERBS AND SUPPLEMENTS WITH SEDATIVE PROPERTIES: Theoretically, concomitant use with herbs that have sedative properties might have additive effects which needs to be taken into account.5,16 Interactions with Drugs: Benzodiazepines: Consult a Medical Herbalist CNS Depressants: Consult a Medical Herbalist Warfarin (Coumadin): Consult a Medical Herbalist Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: Creatinine: Chronic ingestion of German chamomile for two 2 weeks can reduce urinary creatinine output. This effect may be prolonged for up to two weeks after discontinuing German chamomile. The mechanism for this effect is unclear.4 Interactions with Diseases or Conditions: Surgery: Avoid from 2 weeks prior to elective surgery. Dosage/Administration: Oral: For dyspepsia, a specific combination product containing German chamomile (Iberogast, Medical Futures, Inc) and several other herbs has been used in a dose of 1 mL three times daily.7,3,8 For colic in infants, a specific multi-ingredient product containing fennel 164 mg, lemon balm 97 mg, and German chamomile 178 mg (ColiMil, Milte Italia SPA) twice daily for a week has been used.6 Topical: For chemotherapy- or radiation-induced oral mucositis, an oral rinse made with 10-15 drops of German chamomile liquid extract in 100 mL warm water has been used three times daily.2 Comments: German chamomile is an annual herb found throughout Europe and in portions of Asia. German chamomile has a mild apple-like scent. The name "chamomile" is Greek for "Earth apple." Specific References: CHAMOMILE 1. FDA. Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Office of Premarket Approval, EAFUS: A food additive database. Available at: vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/eafus.html. 2. Carl W, Emrich LS. Management of oral mucositis during local radiation and systemic chemotherapy: a study of 98 patients. J Prosthet Dent 1991;66:361-9. 3. Madisch A, Holtmann G, Mayr G, et al. Treatment of functional dyspepsia with a herbal preparation. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Digestion 2004;69:45-52. 4. Wang Y, Tang H, Nicholson JK, et al. A metabonomic strategy for the detection of the metabolic effects of chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) ingestion. J Agric Food Chem 2005;53:191-6. 5. Hormann HP, Korting HC. Evidence for the efficacy and safety of topical herbal drugs in dermatology: part I: anti-inflammatory agents. Phytomedicine 1994;1:161-71. 6. Savino F, Cresi F, Castagno E, et al. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of a standardized extract of Matricariae recutita, Foeniculum vulgare and Melissa officinalis (ColiMil) in the treatment of breastfed colicky infants. Phytother Res 2005;19:335-40. 7. Holtmann G, Madisch A, Juergen H, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial on the effects of an herbal preparation in patients with functional dyspepsia [Abstract]. Ann Mtg Digestive Disease Week 1999 May. 8. Melzer J, Rosch W, Reichling J, et al. Meta-analysis: phytotherapy of functional dyspepsia with the herbal drug preparation STW 5 (Iberogast). Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20:1279-87. 9. Fidler P, Loprinzi CL, O'Fallon JR, et al. Prospective evaluation of a chamomile mouthwash for prevention of 5-FU-induced oral mucositis. Cancer 1996;77:522-5. 10. Maiche AG, Grohn P, Maki-Hokkonen H. Effect of chamomile cream and almond ointment on acute radiation skin reaction. Acta Oncol 1991;30:395-6. 11. Gomaa A, Hashem T, Mohamed M, Ashry E. Matricaria chamomilla extract inhibits both development of morphine dependence and expression of abstinence syndrome in rats. J Pharmacol Sci 2003;92:50-5. 12. Kobayashi Y, Nakano Y, Inayama K, et al. Dietary intake of the flower extracts of German chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) inhibited compound 48/80-induced itch-scratch responses in mice. Phytomedicine 2003;10:657-64. 13. Storr M, Sibaev A, Weiser D, et al. Herbal extracts modulate the amplitude and frequency of slow waves in circular smooth muscle of mouse small intestine. Digestion 2004;70:257-64. 14. Subiza J, Subiza JL, Hinojosa M, et al. Anaphylactic reaction after the ingestion of chamomile tea; a study of cross-reactivity with other composite pollens. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1989;84:353-8. 15. Viola H, Wasowski C, Levi de Stein M, et al. Apigenin, a component of Matricaria recutita flowers, is a central benzodiazepine receptors-ligand with anxiolytic effects. Planta Med 1995;61:213-6. 16. Avallone R, Zanoli P, Puia G, et al. Pharmacological profile of apigenin, a flavonoid isolated from Matricaria chamomilla. Biochem Pharmacol 2000;59:1387-94. | |

Cinnamon

Also Known As: Cassia Cinnamon, Canela de Cassia, Canela Molida, Canelle, Cannelle Scientific Name: Cinnamomum aromaticum, synonyms Cinnamomum cassia, and Cinnamomum People Use This For: Orally, cassia cinnamon is used for type 2 diabetes, gas (flatulence), muscle and Safety: LIKELY SAFE ...when used orally and appropriately. Cassia cinnamon has been Effectiveness: INSUFFICIENT RELIABLE EVIDENCE to RATE Diabetes. There is contradictory evidence about the effectiveness of cassia Mechanism of Action: The applicable parts of cassia cinnamon are the bark and flower. Adverse Reactions: Orally, cassia cinnamon appears to be well-tolerated. No significant side effects Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: HEPATOTOXIC HERBS AND SUPPLEMENTS: There is some concern that Interactions with Drugs: ANTIDIABETES DRUGS <<interacts with>> CASSIA CINNAMON Interaction Rating = Moderate Be cautious with this combination. Cassia cinnamon may lower blood glucose levels, and have additive effects in HEPATOTOXIC DRUGS <<interacts with>> CASSIA CINNAMON Interaction Rating = Moderate Be cautious with this combination. Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: BLOOD GLUCOSE: Cassia cinnamon might lower blood glucose levels and test Interactions with Diseases or Conditions: DIABETES: Cassia cinnamon might lower blood glucose in patients with type Dosage/Administration: ORAL: For type 1 or type 2 diabetes, 1 to 6 grams (1 teaspoon = 4.75 grams) of cassia cinnamon daily for up to 4 months have been used. (8, 13, 18, 19). Editor's Comments: There are a lot of different types of cinnamon. Cinnamomum verum (Ceylon Specific References: Cinnamon 1. lectronic Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21. Part 182 - 2. Lee HS, Ahn YJ. Growth-Inhibiting Effects of Cinnamomum cassia Bark- 3. Koh WS, Yoon SY, Kwon BM, et al. Cinnamaldehyde inhibits lymphocyte 4. Kwon BM, Lee SH, Choi SU, et al. Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity of 5.Anderson RA, Broadhurst CL, Polansky MM, et al. Isolation and 6. Jarvill-Taylor KJ, Anderson RA, Graves DJ. A hydroxychalcone derived from 7. Imparl-Radosevich J, Deas S, Polansky MM, et al. Regulation of PTP-1 and 8. 11347 Khan A, Safdar M, Ali Khan M, et al. Cinnamon improves glucose and 9. De Benito V, Alzaga R. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis from cassia 10.Drake TE, Maibach HI. Allergic contact dermatitis and stomatitis caused by a 11.Onderoglu S, Sozer S, Erbil KM, et al. The evaluation of long-term effcts 12. 3238 13. 14. ress release. Cinnamon capsules to reduce blood sugar are medicinal 15.Miller KG, Poole CF, Pawloski TMP. Classification of the botanical origin 16.He ZD, Qiao CF, Han QB, et al. Authentication and quantitative analysis on 17.Felter SP, Vassallo JD, Carlton BD, Daston GP. A safety assessment of 18.Baker WL, Gutierrez-Williams G, White CM, et al. Effect of cinnamon on 19. Crawford P. Effectiveness of cinnamon for lowering hemoglobin A1C in 20. Blevins SM, Leyva MJ, Brown J, et al. Effect of cinnamon on glucose and lipid | |

Cleavers

Bedstraw, Catchweed, Cleavers, Gallium, Goose Grass, Gosling Weed, Robin-Run-in-the-Grass, Scratchweed, Stick-a-Back, Sticky Willy. Scientific Name: Galium aparine. Family: Rubiaceae. People Use This For: Clivers is used as a diuretic, a mild astringent, for dysuria, lymphadenitis, psoriasis, and specifically for enlarged lymph nodes. Safety: No concerns regarding safety when used orally and appropriately.13 There is no documented toxicity.14 Pregnancy and Lactation: Refer to a Medical Herbalist. Effectiveness: There is insufficient scientific information available about the effectiveness of clivers. Mechanism of Action: The applicable parts of clivers are the dried or fresh above ground parts. Cleavers contain tannins, which are reported to have astringent properties.14 Adverse Reactions: None reported. Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: None known. Interactions with Drugs: None known. Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: None known. Dosage/Administration: Dr Clare’s Blends: 1gm per day. Oral: Typical doses are 2-4 grams dried above ground parts three times daily, or one cup tea (steep 2-4 grams herb in 150 mL boiling water 5-10 minutes, strain) three times daily.14 Liquid extract (1:1 in 25% alcohol) 2-4 mL three times daily.14 Spedific References: CLIVERS 13. McGuffin M, Hobbs C, Upton R, Goldberg A, eds. American Herbal Products Association's Botanical Safety Handbook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, LLC 1997. 14. Newall CA, Anderson LA, Philpson JD. Herbal Medicine: A Guide for Healthcare Professionals. London, UK: The Pharmaceutical Press, 1996. | |

CORE REFERENCES

R5. Grases, F., March, J. G., Ramis, M. & Costa-Bauzá, A. (1993) The influence of Zea mays on urinary risk factors for kidney stones in rats.

| |

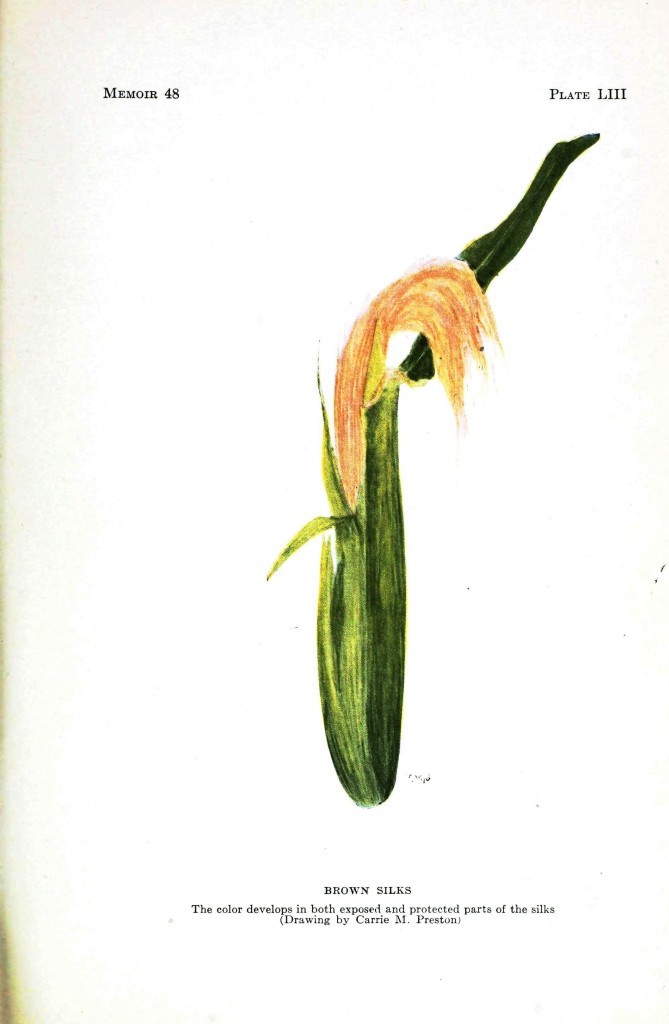

Cornsilk

Indian Corn, Yu Mi Xiu, Zea. Scientific Name: Zea mays. Family: Poaceae/Gramineae. People Use This For: Orally, corn silk is used for cystitis, urethritis, bedwetting, inflammation of the prostate, acute and chronic inflammation of the urinary system. Safety: No concerns regading safety, available studies validate this statement, when used orally in amounts commonly found in foods. Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status in the US.6 No concerns regarding safety when used orally and appropriately in medicinal amounts.7 Pregnancy and Lactation: Refer to a Medical Herbalist Effectiveness: There is not enough scientific information available to comment about the effectiveness of corn silk. Mechanism of Action: Corn silk contains tannins, which are astringent, and cryptoxanthin, which has vitamin A activity.8 Diuretic. Demulcent (mucilagenous). Choleretic (promotes bile flow). The diuretic and choleretic action has been demonstrated in animal studies.R5 In China it is used for Hepato-Biliary Disease.R6,R7 Adverse Reactions: None. Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: Herbs and Supplements with Hypotensive Effects: Corn silk is thought to have hypotensive effects, may have an additive effect with blood pressure lowering agents. Interactions with Drugs: Antidiabetes Drugs: Theoretically, because some evidence suggests corn silk can reduce blood glucose levels, excessive amounts might interfere with diabetes therapy.R1 pp.222 Diuretic Drugs: Additive Effect.R4 pp.192,204,215 Lithium: Because of Diuretic effect. Warfarin (Coumadin): Corn silk contains vitamin K. Individuals taking warfarin should consume a consistent daily amount to maintain consistent anticoagulation.9 Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: None known. Interactions with Diseases or Conditions: None within normal dose range. Dosage/Administration: Oral: 4-8 grams dried style/stigma three times daily, or one cup tea (steep 0.5 grams dried corn silk in 150 mL boiling water 5-10 minutes, strain) several times daily.8,10 Liquid extract of maize stigmas, 4-8 mL.8 Tincture (1:5 in 25% alcohol), 5-15 mL three times daily. 8 Syrup of maize stigmas, 8-15 mL.8 Dr Clare’s Comments: Corn silk is the silky threads that surround the ear of sweetcorn. It is one on the few herbs that are more effective dried, probably because they have such a high water content it would take a lot of them to make an effective fresh infusion. It would be nice to think that Corn Silk would ‘treat’ high blood pressure/diabetes however it is likely to be helpful in the way an extra portion of fruit or vegetables are helpful. It will not reduce a normal blood sugar or a normal Blood Pressure in my experience. Nor has it been reported, these are theoretical considerations. Specific References: CORN SILK 6. FDA. Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Office of Premarket Approval, EAFUS: A food additive database. Available at: vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/eafus.html. 7. McGuffin M, Hobbs C, Upton R, Goldberg A, eds. American Herbal Products Association's Botanical Safety Handbook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, LLC 1997. 8. Newall CA, Anderson LA, Philpson JD. Herbal Medicine: A Guide for Healthcare Professionals. London, UK: The Pharmaceutical Press, 1996. 9. Brinker F. Herb Contraindications and Drug Interactions. 2nd ed. Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications, 1998. Wichtl MW. Herbal Drugs and Phytopharmaceuticals. Ed. N.M. Bisset. 10. Stuttgart: Medpharm GmbH Scientific Publishers, 1994 | |

Couchgrass

Agropyron, Coughgrass, Cutch, Dog Grass. Scientific Name: Agropyron repens. Family: Poaceae/Gramineae. People Use This For: It is used orally to treat cystitis, urethritis, prostatitis, benign prostatic hypertrophy and kidney stones. Safety: No concerns regarding safety, available studies validate this statement, when consumed in amounts commonly found in foods.11 Pregnancy and Lactation: Refer to a Medical Herbalist. Effectiveness: Not enough scientific information gather to offer a comment. Mechanism of Action: Diuretic.R8 pp.18,R1 pp.222 Adverse Reactions: None known Interactions with Herbs & Supplements: None known. Interactions with Drugs: None known. Interactions with Foods: None known. Interactions with Lab Tests: None known. Interactions with Diseases or Conditions: None known. Dosage/Administration: Oral: For treating ulcerative colitis, 100 mL of wheatgrass juice daily for 1 month has been used.12 DrClare’s Blends: Specific References: COUCHGRASS 11. Rauma AL, Nenonen M, Helve T, et al. Effect of a strict vegan diet on energy and nutrient intakes by Finnish rheumatoid patients. Eur J Clin Nutr 1993;47:747-9. 12. Ben-Arye E, Golden E, Wengrower D, et al. Wheat grass juice in the treatment of active distal ulcerative colitis a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002;4:444-9. | |

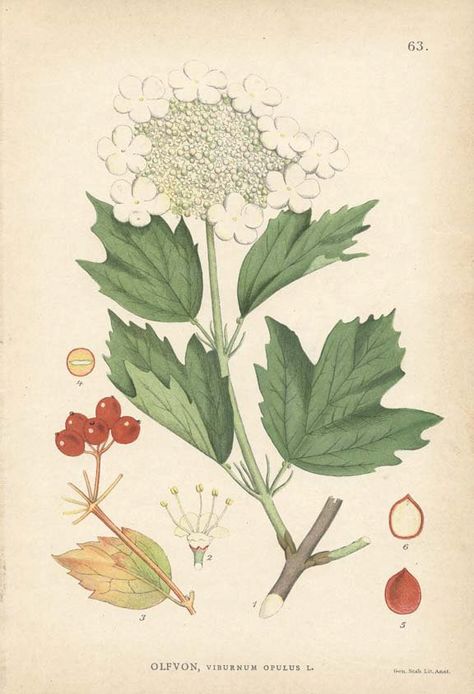

Cramp Bark

Also known as: Common Guelder-Rose, Cranberry Bush. Scientific Name: Viburnum opulus. Botanical Family: Adoxaceae/Viburnaceae (formerly known as Caprifoliaceae). Part used: Bark and root bark.

Traditional Use. Cramp bark has antispasmodic (relieves muscle spasms), anti-inflammatory (relieves inflammation), nervine (calms and soothes the nerves), hypotensive (lowers blood pressure), astringent (causes local contraction), emmenagogic (induces menstruation ), and sedative (reduces activity and excitement) properties.

Safety. There are no reports of safety concerns regarding Cramp Bark.